What's in a Token? – An OpenID Connect Primer, Part 3 of 3

In the previous two installments of this OpenID Connect (OIDC) series, we dug deep into the OIDC flow types and saw OIDC in action using a playground found at: https://okta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com/.

In this third and final installment, we’ll look at what’s encoded into the various types of tokens and how to control what gets put in them. JWTs, have the benefit of being able to carry information in them. With this information available to your app you can easily enforce token expiration and reduce the number of API calls. Additionally, since they’re cryptographically signed, you can verify that they have not been tampered with.

The source code that backs the site can be found at: https://github.com/oktadeveloper/okta-oidc-flows-example.

There are two primary sources for information relating to identity as dictated by the OIDC spec. One source is the information encoded into the id_token JWT. Another is the response from the /userinfo endpoint, accessible using an access_token as a bearer token. At Okta, we’ve chosen to make our access tokens JWTs as well, which provides a third source of information. (You’ll see this in many OIDC implementations.)

There are a lot of combinations of query parameters in the /authorization request that determine what information will be encoded into an id_token. The two query parameters that impact what will ultimately be found in returned tokens and the /userinfo endpoint are response_type and scope.

OIDC Response Types

For the moment, we’ll set aside scope and focus on response_type. In the following examples, we use only the scopes, openid (required) and email. We’ll also work with the implicit flow, since that gives us back tokens immediately.

Given this request:

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/authorize?client_id=0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7&response_type=token&scope=openid+email&state=aboard-insect-fresh-smile&nonce=c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fokta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com%2Fflow_result

Notice that response_type=token will yield us an access_token. A particular format is not required in the OIDC spec for access tokens, but at Okta we use JWTs. Looking inside the returned token, we see:

{

"active": true,

"scope": "openid email",

"username": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"exp": 1501531801,

"iat": 1501528201,

"sub": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"aud": "test",

"iss": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"jti": "AT.upPJqU-Ism6Fwt5Fpl8AhNAdoUeuMsEgJ_VxJ3WJ1hk",

"token_type": "Bearer",

"client_id": "0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7",

"uid": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7"

}

This is mainly resource information, including an expiration (exp) and a user id (uid).

If we want to get identity information for the user, we must hit the /userinfo endpoint using the access_token as a bearer token. Here’s what that looks like using HTTPie:

http https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/userinfo Authorization:"Bearer eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsImtpZCI6Ik93bFNJS3p3Mmt1Wk8zSmpnMW5Dc2RNelJhOEV1elY5emgyREl6X3RVRUkifQ..."

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"email": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"email_verified": true

}

We get back the sub, email and email_verified claims. This is because of the default scope=openid+email from the original request. We’ll look at some more detailed responses in the scopes section.

Let’s try another request:

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/authorize?client_id=0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7&response_type=id_token&scope=openid+email&state=aboard-insect-fresh-smile&nonce=c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fokta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com%2Fflow_result

This time, I’m asking for an ID token by using response_type=id_token. The response is a JWT (as required by the OIDC spec) with this information encoded into it:

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"email": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"ver": 1,

"iss": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"aud": "0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7",

"iat": 1501528456,

"exp": 1501532056,

"jti": "ID.4Mmzy2kj5_B8nGZ_PT4dt8-fzu1tA2W3C5dbEF-N6Us",

"amr": [

"pwd"

],

"idp": "00o1zyyqo9bpRehCw1t7",

"nonce": "c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f",

"email_verified": true,

"auth_time": 1501528157

}

Notice that we have the sub and emailclaims encoded directly in the JWT. In this type of implicit flow, we have no bearer token to use against the /userinfo endpoint, so the identity information is baked right into the JWT.

Finally, let’s look at the last type of implicit flow:

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/authorize?client_id=0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7&response_type=id_token+token&scope=openid+email&state=aboard-insect-fresh-smile&nonce=c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fokta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com%2Fflow_result

Here, we are requesting both an id_token and an access_token in the response.

Our access_token has the same claims as before. The id_token has the following:

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"email": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"ver": 1,

"iss": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"aud": "0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7",

"iat": 1501528536,

"exp": 1501532136,

"jti": "ID.fyybPizTmYLoQR20vlR7mpo8WTxB7JwkxplMQom-Kf8",

"amr": [

"pwd"

],

"idp": "00o1zyyqo9bpRehCw1t7",

"nonce": "c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f",

"auth_time": 1501528157,

"at_hash": "T7ij7o69gBtjo6bAJvaVBQ"

}

Notice that there’s less information in the id_token this time (in this case, there’s no email_verified claim). Because we also requested the access_token, it’s expected that we will get the rest of the available identity information (based on scope) from the /userinfo endpoint. In this case, it yields the same information as before when we only requested the access_token

OIDC Scopes

Combining all the available scopes with all the possible response types yields a large set of information to present: 48 combinations, to be exact. First, I’ll enumerate what each scope yields and then we’ll look at a few real world examples combining request_type and scope.

The first thing to note is that the different scopes have an impact on the information encoded in an id_token and returned from the /userinfo endpoint. Here’s a table of scopes and resultant claims. More information can be found in Section 5.4 of the OIDC Spec

| scope | resultant claims |

|---|---|

| openid | (required for all OIDC flows) |

| profile | name, family_name, given_name, middle_name, nickname, preferred_username |

| profile (cont’d) | profile, picture, website, gender, birthdate, zoneinfo, locale, updated_at |

| email, email_verified | |

| address | address |

| phone | phone_number, phone_number_verified |

Let’s try each of our implicit flows with all the possible (default) scope types.

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/authorize?client_id=0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7&response_type=token&scope=openid+profile+email+address+phone&state=aboard-insect-fresh-smile&nonce=c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fokta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com%2Fflow_result

The only difference in the resultant access_token compared to before is that all the scopes are encoded into the scp array claim.

This time, when I use the access_token to hit the /userinfo endpoint, I get back more information:

http https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/userinfo Authorization:"Bearer eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsImtpZCI6Ik93bFNJS3p3Mmt1Wk8zSmpnMW5Dc2RNelJhOEV1elY5emgyREl6X3RVRUkifQ..."

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"name": "Okta OIDC Fun",

"locale": "en-US",

"email": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"preferred_username": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"given_name": "Okta OIDC",

"family_name": "Fun",

"zoneinfo": "America/Los_Angeles",

"updated_at": 1499922371,

"email_verified": true

}

Note: While it’s not the complete list of claims defined from profile scope, it’s all the claims for which my user in Okta has a value.

Let’s try just the id_token implicit flow (still with all the default scopes):

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/authorize?client_id=0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7&response_type=id_token&scope=openid+profile+email+address+phone&state=aboard-insect-fresh-smile&nonce=c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fokta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com%2Fflow_result

Here’s what’s encoded into the id_token I get back:

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"name": "Okta OIDC Fun",

"locale": "en-US",

"email": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"ver": 1,

"iss": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"aud": "0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7",

"iat": 1501532222,

"exp": 1501535822,

"jti": "ID.Zx8EclaZmhSckGHOCRzOci2OaduksmERymi9-ad7ML4",

"amr": [

"pwd"

],

"idp": "00o1zyyqo9bpRehCw1t7",

"nonce": "c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f",

"preferred_username": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"given_name": "Okta OIDC",

"family_name": "Fun",

"zoneinfo": "America/Los_Angeles",

"updated_at": 1499922371,

"email_verified": true,

"auth_time": 1501528157

}

All the (available) identity information is encoded right into the token, since I don’t have a bearer token to hit the /userinfo endpoint with.

Finally, let’s try the last variant of the Implicit Flow: response_type=id_token+token:

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/authorize?client_id=0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7&response_type=code+id_token+token&scope=openid+profile+email+address+phone&state=aboard-insect-fresh-smile&nonce=c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f&redirect_uri=https%3A%2F%2Fokta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com%2Fflow_result

In this case, we have some of the claims encoded into the id_token:

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"name": "Okta OIDC Fun",

"email": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"ver": 1,

"iss": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"aud": "0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7",

"iat": 1501532304,

"exp": 1501535904,

"jti": "ID.1C2NQext2hM0iJy55cLc_Ryc45urVYC1wJ0S-KebkpI",

"amr": [

"pwd"

],

"idp": "00o1zyyqo9bpRehCw1t7",

"nonce": "c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f",

"preferred_username": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"auth_time": 1501528157,

"at_hash": "GB5O9CpSSOUSfVZ9CRekRg",

"c_hash": "mRNStYQm-QU4rwcfv88VKA"

}

If we use the resultant access_token to hit the /userinfo endpoint, in this case, we get back:

http https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/userinfo Authorization:"Bearer eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsImtpZCI6Ik93bFNJS3p3Mmt1Wk8zSmpnMW5Dc2RNelJhOEV1elY5emgyREl6X3RVRUkifQ..."

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"name": "Okta OIDC Fun",

"locale": "en-US",

"email": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"preferred_username": "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com",

"given_name": "Okta OIDC",

"family_name": "Fun",

"zoneinfo": "America/Los_Angeles",

"updated_at": 1499922371,

"email_verified": true

}

This rounds out all the identity information that was requested in the scopes.

Custom Scopes and Claims

The OIDC spec accommodate custom scopes and claims. The ability to include custom claims in a token (which is cryptographically verifiable) is an important capability for identity providers. Okta’s implementation provides support for this.

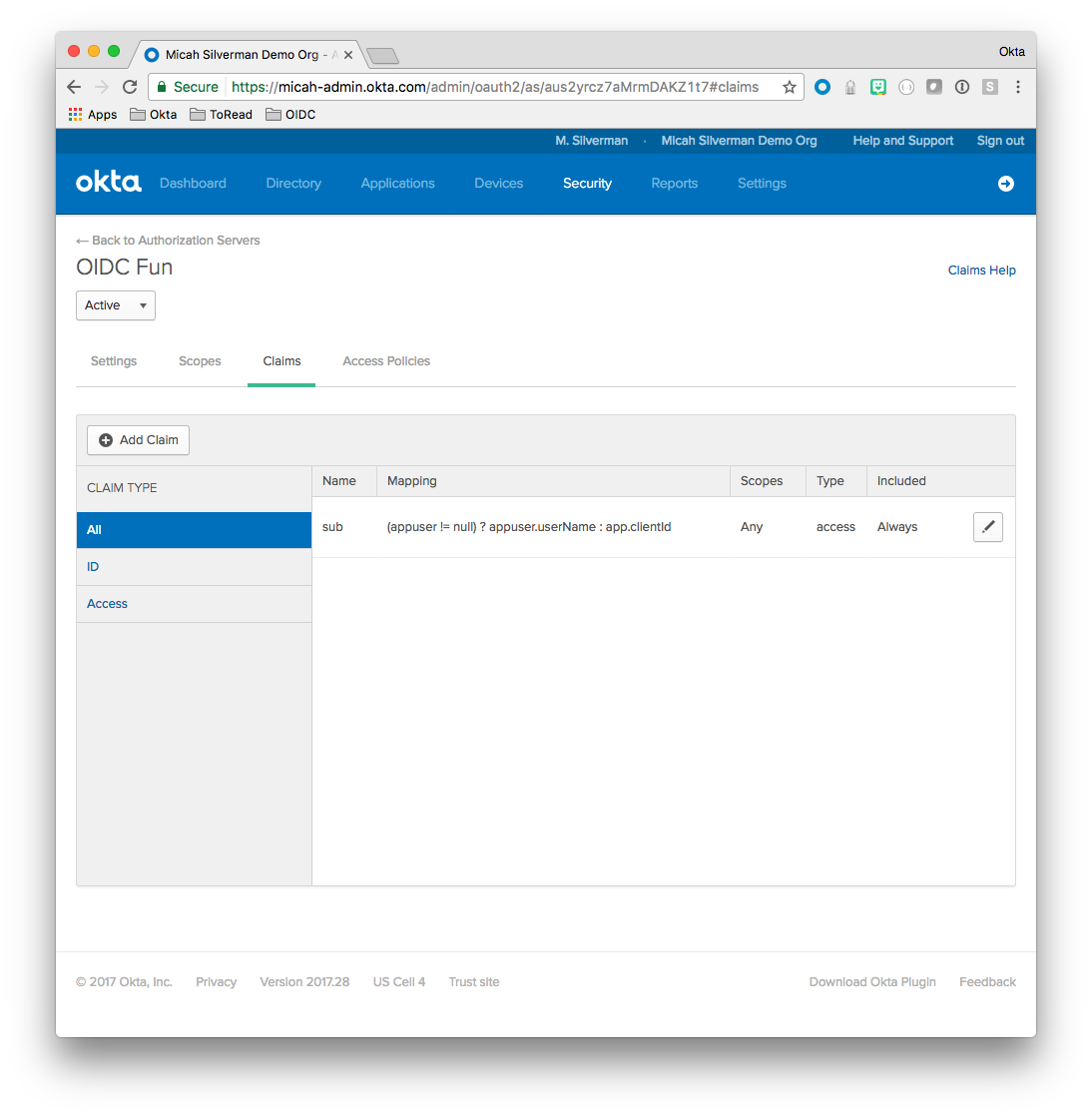

The screenshot below shows my Authorization Server’s Claims tab:

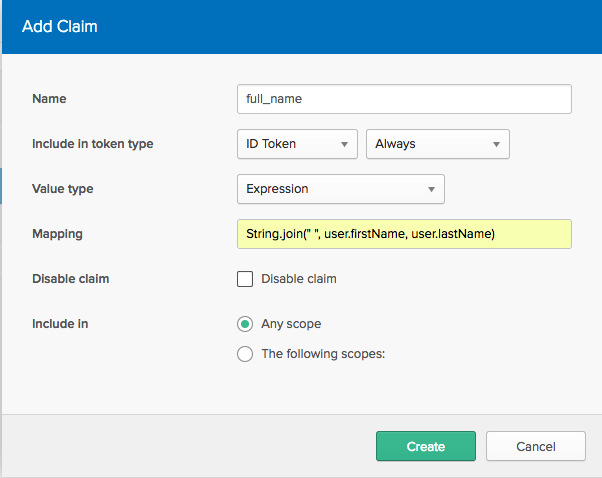

Clicking the “Add Claim” button brings up a dialog:

In the above screenshot, the custom claim is defined using Okta’s Expression Language. Unique to Okta, the expression language is a flexible way to describe rules for building a property to include (or not) in custom claims.

Using the implicit flow with response_type=id_token and scope=openid+profile, we now get back an id_token with these claims encoded in it:

{

"sub": "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"ver": 1,

"iss": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"aud": "0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7",

"iat": 1501533536,

"exp": 1501537136,

"jti": "ID.TsKlBQfGmiJcl2X3EuhzyyLfmzqi0OCd66rJ3Onk7FI",

"amr": [

"pwd"

],

"idp": "00o1zyyqo9bpRehCw1t7",

"nonce": "c96fa468-ca1b-46f0-8974-546f23f9ee6f",

"auth_time": 1501528157,

"at_hash": "hEjyn3mbKjuWanuSAF-z4Q",

"full_name": "Okta OIDC Fun"

}

Notice the full_name claim present in the id_token.

Verifying Tokens

Access tokens can be verified by hitting the /introspect endpoint. For an active token, you get a response like this:

http --auth <OIDC Client ID>:<OIDC Client Secret> -f POST \

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/introspect \

token=eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsImtpZCI6Ik93bFNJS3p3Mmt1Wk8zSmpnMW5Dc2RNelJhOEV1elY5emgyREl6X3RVRUkifQ...

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"active": true,

"aud": "https://afitnerd.com/test",

"client_id": "xdgqP32nYN148gn3gJsW",

"exp": 1498517509,

"fullName": "Micah Silverman",

"iat": 1498513909,

"iss": "https://micah.oktapreview.com/oauth2/aus9vmork8ww5twZg0h7",

"jti": "AT.JdXQPAuh-JTqhspCL8nLe2WgbfjcK_-jmlp7zwaYttE",

"scope": "openid profile",

"sub": "micah+okta@afitnerd.com",

"token_type": "Bearer",

"uid": "00u9vme99nxudvxZA0h7",

"username": "micah+okta@afitnerd.com"

}

Since it requires the OIDC client ID and secret, this operation would typically be done in an application server where it’s safe to have those credentials. You would not want something like an end-user web or mobile application to have access to the OIDC client secret.

If the token parameter is invalid or expired, the /introspect endpoint returns this:

http --auth <OIDC Client ID>:<OIDC Client Secret> -f POST \

https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/introspect \

token=bogus

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"active": false

}

ID tokens can be verified using the JWK endpoint. JWK is a JSON data structure that represents a crypto key. The JWK endpoint is exposed from the OIDC “well known” endpoint used for API discovery. This returns a lot of information. Here’s an excerpt:

http https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/.well-known/openid-configuration

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"authorization_endpoint": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/authorize",

...

"introspection_endpoint": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/introspect",

...

"issuer": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"jwks_uri": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/keys",

...

"userinfo_endpoint": "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/userinfo"

}

Some of the endpoints, such as /userinfo and /authorize, should look familiar by now. The one we’re interested in is the /keys endpoint shown in jwks_uri.

http https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7/v1/keys

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

...

{

"keys": [

{

"alg": "RS256",

"e": "AQAB",

"kid": "cbkhWG0YmFsGiNO1LEkWSEszDCTNfwvJPpXxuVf_kX0",

"kty": "RSA",

"n": "g2XQgdyc5P6F4K26ioKiUzrdgfy90eBgIbcrKkspKZmzRJ3CIssv69f1ClJvT784J-...",

"use": "sig"

}

]

}

Notice the kid claim. It matches the kid claim in the header from our id_token:

{

"typ": "JWT",

"alg": "RS256",

"kid": "cbkhWG0YmFsGiNO1LEkWSEszDCTNfwvJPpXxuVf_kX0"

}

We can also see that the algorithm used is RS256. Using the public key found in the n claim along with a security library, we can confirm that the ID token has not been tampered with. All of this can be done safely on an end-user SPA, mobile app, etc.

Here’s a Java example that uses the claims from the jwks_uri above to verify an id_token: https://github.com/dogeared/JWKTokenVerifier

java -jar target/jwk-token-verifier-0.0.1-SNAPSHOT-spring-boot.jar \

eyJhbGciOiJSUzI1NiIsImtpZCI6Ik93bFNJS3p3Mmt1Wk8zSmpnMW5Dc2RNel... \

g2XQgdyc5P6F4K26ioKiUzrdgfy90eBgIbcrKkspKZmzRJ3CIssv69f1ClJvT784J-... \

AQAB

Verified Access Token

{

"header" : {

"alg" : "RS256",

"kid" : "cbkhWG0YmFsGiNO1LEkWSEszDCTNfwvJPpXxuVf_kX0"

},

"body" : {

"ver" : 1,

"jti" : "AT.LT9cRL_Kzd3T8Izw_ONZxHJ5xGBPD0m13iiEIDK_Nbw",

"iss" : "https://micah.okta.com/oauth2/aus2yrcz7aMrmDAKZ1t7",

"aud" : "test",

"iat" : 1501533536,

"exp" : 1501537136,

"cid" : "0oa2yrbf35Vcbom491t7",

"uid" : "00u2yulup4eWbOttd1t7",

"scp" : [ "openid" ],

"sub" : "okta_oidc_fun@okta.com"

},

"signature" : "ZV_9tYxt4v4bp9WEEDu038b7v_OHsbMZw13daR1s5_tI56oayBgJlnqf-..."

}

If any part of the id_token JWT had been tampered with, you would see this instead:

io.jsonwebtoken.SignatureException: JWT signature does not match locally computed signature. JWT validity cannot be asserted and should not be trusted.

Verifying JWT’s using the /introspect endpoint and using JWKs is a powerful component of OIDC. It allows for a high degree of confidence that the token has not been tampered in any way. And, because of that, information contained within – such as expiration – can be safely enforced.

How I Learned to Love OpenID Connect

When OIDC was first released and early implementers, such as Google, adopted it, I thought: “I just got used to OAuth 2.0. Why do I have to learn a new thing that rides on top of it?”

It took some time, but here is what I consider to be the important takeaways:

- OIDC formalizes a number of things left open in OAuth 2.0. Things like: specific token formats (id_token) and specific scopes and claims.

- There’s explicit support for Authentication and Authorization. OAuth 2.0 was always presented purely as an authorization framework, but people would get confused with certain flows that allowed for authentication.

- There’s a clear separation between identity (

id_tokenand/userinfo) and access to resources (access_token). - The different flows provide clean use case implementations for mobile apps, SPAs, and traditional web apps.

- It’s inherently flexible. It’s easy to provide custom scopes and claims and to dictate what information should be encoded into tokens beyond the default specification.

All the code used in this series can be found on github. You can use the OIDC sample app to exercise the various flows and scopes discussed throughout these posts. It’s at: https://okta-oidc-fun.herokuapp.com/. The entire final OIDC spec can be found here. And you can learn more about OAuth 2.0 at oauth.com.

The whole series is live now. Part 1 is here. Part 2 is here. If you’re looking for other security-focused articles, you may want to check out our new security site, where we’re publishing lots of other in-depth security pieces.

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.