The Development Environment of the Future

Here’s a thought exercise for you: How will we develop software in the near future? Below, I’ll lay out what I think that looks like. Some of the things in this post exist in some form already. And some things don’t exist… yet.

To begin, I’m going to start with a short story about someone using this futuristic development environment:

A Story

Imagine Viola. She is a software developer at Sunnyvale Systems, a logistics company. Viola is on the phone with a customer, who called in to report a bug in their route planning software. The customer is Polish, and unable to type the Polish letter “Ś” into text fields in the Sunnyvale Systems user interface. It takes a little while to figure out what the bug is, but Viola is able to get to the bottom of the issue by connecting her development environment directly to the customer’s browser session.

Viola tries a few things with the customer on the line. “Try now,” she says, and the customer tries again. No dice. A few more changes, and Viola asks the customer to try again, repeating this until she finds the solution—the Sunnyvale Systems UI ignores the “Ctrl+S” keyboard combination to prevent the “Save webpage” dialog from opening for people who are used to Microsoft Word.

However, Polish keyboards send “Ctrl+Alt+S” when a user types “Right Alt+S” to enter the “Ś” letter, and the logic to ignore “Ctrl+S” interferes with this. The fix is to only ignore “Ctrl+S” if “Alt” isn’t pressed as well.

Once Viola figures out what the issue is, it’s time to move her changes to the production system. To do this, Viola points her development environment at the production system, makes the change, but gets a warning that her updated change has no tests for it. So she quickly adds a test to make sure that the Ctrl+Alt+S key combination is not ignored. About 500 milliseconds after that test passes, her change is live. She asks the customer to reload his app one more time and try typing “Ś” —it works, and the customer hangs up, a little shocked that his issue was fixed so quickly.

Why Isn’t the “Future” Here Already?

Computers have barely achieved even a fraction of their potential. Most of what is holding back the potential of computers is not the technology itself, it’s the mental models that humans use to interact with computers.

Even with all of the advances that we’ve made since 1981, the way that we use computers hasn’t really changed much since then. We’ve made astounding advances in processor, storage, and display technology since then. In fact, computation is essentially free today. But in spite of all those changes, the way that we think about, with, and for computers hasn’t changed. The computers that we use today are essentially fancy typewriters.

That may sound like hyperbole, but let’s consider some examples of ways that developers interact with their computers today:

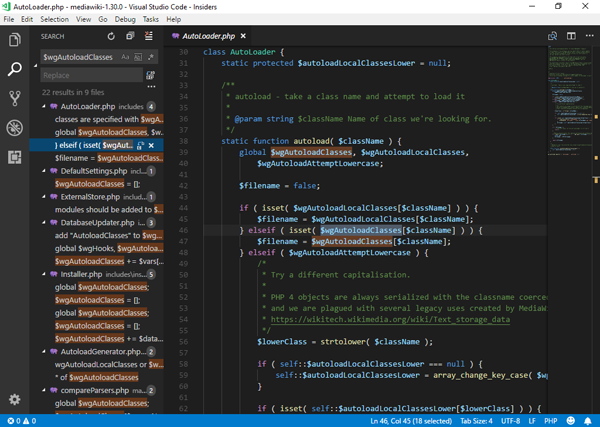

|

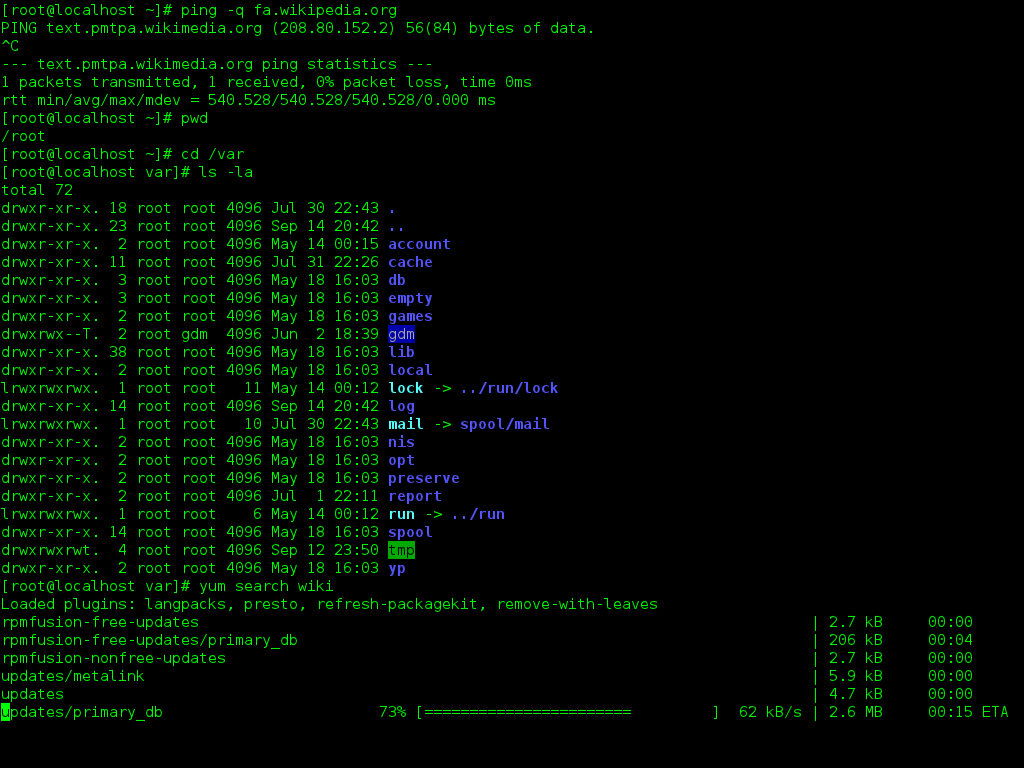

|

On the left, we have Visual Studio Code, a popular program used to write code. On the right, we see a command line interface, used to run, build, and test code.

Each program uses fixed-width fonts. And furthermore, the picture on the right is literally from a program that simulates a teletype, a “typewriter” that could talk with other similar typewriters over the telephone. It’s another example of the saying “We shape our tools, and our tools shape us.” Programmers in 2020 use the same computer interface that the authors of UNIX used to write UNIX 50 years earlier:

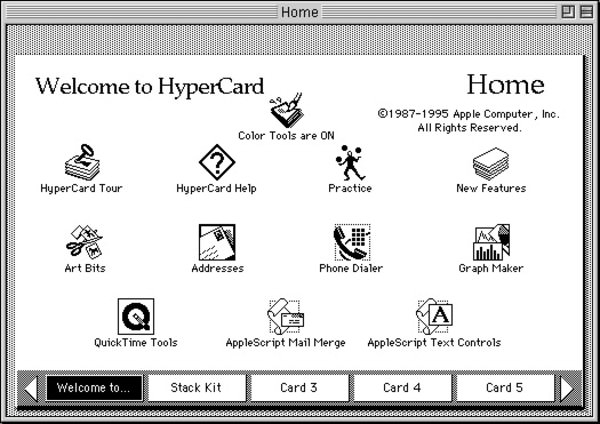

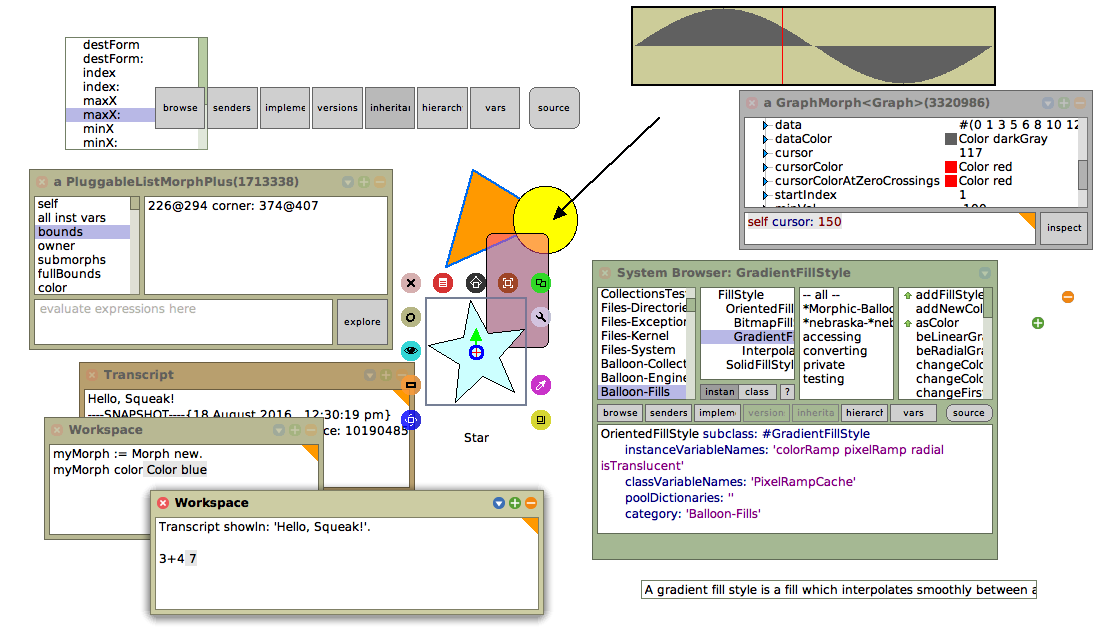

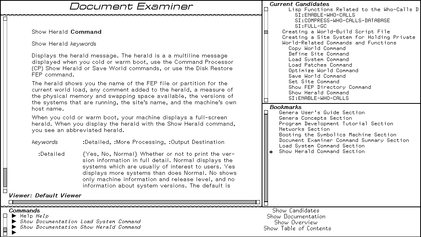

There have been many attempts to break free of the typewriter interface for computers, some of the better examples of this include HyperCard, Squeak, and the Genera OS.

|

|

|

However, for various reasons none of these interfaces took off. For better or worse, text based interfaces are here to stay.

What does any of this have to do with “the development environment of the future,” you may ask? Well, I strongly believe that as long as we’re using a screen, keyboard, and mouse to interact with the computer, we simply can’t ignore the effects of path dependence.

We will have to make compromises while still striving for the more ideal environments that things like HyperCard, Squeak, and Genera all point to. Simply put, a pragmatic approach is required.

Another thing to consider here is that the internet has changed the way that we work with and think about our computers. In particular, the internet changed software development from a “top down” approach to a “ground up” one. Microsoft, which was founded before (and famously ignored) the internet, perfected the “top down” style of software development and distribution. What they failed to see, and tried to stop, was the “ground up” approach that Linux and the Free Software movement epitomized. A popular analogy from the early 2000s was “the cathedral and the bazaar,” though I’ve found it more useful to think of Free Software as a Cambrian explosion of software, where software is selected based on ease of use and ease of understanding, instead of ease of acquisition. In short, the current state of the computational medium means that old interfaces and pragmatism win.

The concept of “a computer as a fancy typewriter” is here to stay for now. Let’s make the best of it.

Towards a More Ideal Development Environment

You can split the approaches used to program a computer into roughly two camps: batch processing and interactive Computing. Batch processing is what banks used to do in the days before computers: Stop everything while you focus on processing all of the day’s financial transactions. (This is where “banker’s hours” come from.)

Batch processing is sort of like making soup by following a recipe exactly, down to the nanoliter. In terms of software development, the batch processing approach is where the programmer takes great pains to write software that works right the first time it’s written. In contrast, the interactive computing approach is sort of like making up a soup as you go along, constantly tasting what’s in the pot as you mix in ingredients. In software development, the interactive computing approach is one where the computer is constantly helping the programmer as code is being written. When computers were as big as rooms and cost as much as houses, it made sense to use the batch processing approach to write software—the computing time was worth more than the programmer time. Now that computers are basically free, it’s the programmer’s time that is worth more. Now it makes sense to have the computer help write the software too.

This brings us to the first aspect of the development environment of the future: A fully interactive environment, one where the programmer works with the computer, not for the computer.

We see hints of this today: Microsoft Word will highlight suspected mispellings or grammar error, programmers can have their development environments warn them if there are syntactical errors in their code. But we still have a long way to go. One thing missing in particular is automated testing. Today, a production test suite is considered “fast” if it completes in a minute or so. However, a minute is roughly 59.9 seconds too long. Automated tests should be so fast that they can run as the programmer types.

On a related note, much of modern-day programming takes too long. Instead of measuring software operations using hours, or minutes, we should be using milliseconds. Changes to tests, database schemas, production systems, source control… all of these things should happen in milliseconds.

Also obviously missing from the list of things that computers can do to help programmers, is treating all code as a graph, rather than a linear text file. “Lines of text” is yet another vestigial appendage from the teletype era. The way that a programmer interfaces with a computer today is something like this: Humans write code as linear text, which is parsed into a graph, compiled into a linear set of instructions, which is parsed by the CPU into a graph, to be executed. Many programming languages and programming environments are making it easier to see, reason about, and work with code as a graph (or abstract syntax tree), and we already know about a lot of great things you can do when you have access to code as a graph, like Jester for Java, code slicing, LLVM, etc. The issue is simply that thinking of code as a graph is another mental model to adopt, and the benefits are hard to attain if your programming language doesn’t expose the abstract syntax tree in an easy-to-use and easy-to-understand way.

These are just a few examples of already explored computer science research that we have yet to adopt, and are particularly interesting when taking a look into the near future. If we have a development system where tests and other changes happen in milliseconds and code is a graph, then we can imagine how a system with those characteristics might look—a system with no “environments,” no development, testing, or production. No servers. No databases. Just code that runs everywhere.

If this sounds ridiculous, consider that much of what I describe is already available today!

Existing Visions of the Future of Software Development

Parts of what I describe above exist already. Glitch and repl.it are online, interactive software development environments where changes to code happens instantly. Companies like Fastly, CloudFlare, and Vercel have compelling “serverless” platforms, as do AWS, GCP, and Azure. You could build part of what I described if you, for example, hooked up Glitch to some fast unit tests and, when the code passed the tests, had it automatically published to CloudFlare workers.

Finally, if you’re willing to learn a custom (OCaml inspired) programming language, you can see what the future of programming looks like by using Dark which (among other things) allows you to edit code as a graph, makes updates to production in milliseconds, and doesn’t require you to think about servers or databases.

Where to Go from Here?

If I could encourage you to take only one thing from this post, it would be this:

When you are building systems for programmers, build systems where the programmer works with the computer, where the computer augments the programmer’s intelligence, rather than tries to replace it.

Comment below with what you think the development environment of the future will look like—and what parts are already here. Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and subscribe to our YouTube channel for great tutorials and observations from the engineering field!

Thanks to Gabriel Sroka and Paul Biggar for reading drafts of this post.

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.