How to Adapt Your .NET App for SameSite

Have you run across an error message vaguely referencing SameSite in your .NET Apps? Read on, it’s time for a change to your code - and I’ll explain why.

I like cookies, both the custard stuffed and the dry ones (which I use to dunk in my coffee or tea). This post is very much about cookies - only not the delicious, culinary ones. As in many other cases (think of the web, for example), the computer and internet world has re-branded some common language terms to identify new concepts in the IT domain with perceived similarities. Even the term computer was before used to refer human beings whose job was to compute calculations (have you watched Hidden Figures?)

In the web (and I mean World-Wide-Web), HTTP cookies (simply cookies in the rest of the post) are little pieces of data that you don’t interact directly with.

When you surf with your browser for example, under the hood many internet transactions occur between your computer and one or more other computers located elsewhere. It is a classic client-server scenario, where your computer issues requests to remote ones and (hopefully) gets answers from them.

If we look deeper, though, we discover that the answers can contain more information than the one you see in the browser. Information that is not meant to be rendered or presented, but it’s fundamental for the lower-level handshake between the two endpoints. Among these additional information elements, there are so-called “cookies”.

Cookies? Why We Need Them

On the web, computers are known by their addresses, which are basically numbers (32 bits in IPv4, or 128 in IPv6). So let’s suppose that you and I are clients of the same bank and that our bank exposes their services on the web with an endpoint having address “1”. I have a computer with address “2” and your computer has address “3”. Then, when I request my bank statement, the bank server receives a request from address “2”, so it knows which statement to respond with. Similarly, if you issue the same request, the server will receive it from address “3”, and you will receive your (not mine), statement. We are good and safe, right?

Well, what if I can access your computer? And what if I can change my computer’s address to “3” and pretend to be you? No, this is not safe enough. Let’s say that the bank server requires that you and I send some secret identity information with the request. So, before clicking on the “Get Statement” button on the page, I have to write my name and a password, which is sent to the server with the statement request. The server will check the identity and respond accordingly. Better, right?

Sort of!

The problem is that with this policy we need to write user name and password every time we make a request in the bank portal. I don’t know about you, but I would get annoyed quickly and hate internet banking.

Ok, let’s allow the server to “remember”. Before having access to your bank account, you perform a login transaction, insert your credentials, and ask the server to remember you. After that, you are no longer required to insert your credentials, the server “remembers” that requests from address “3” are from you. Of course, I could still change my address to “3” and steal your money… still no good.

That’s why, when you log in on your website, what really happens is that the server builds up a piece of data (usually called session token) bound to your identity, and sends it back to the browser. This token is not shown by the browser, but safely stored locally in your computer. From this point on, every time your browser issues requests to the bank server, it will embed this information into the request, and the server will know what session that request is coming from. If I want to access your account, I not only need to change my address but also know your session token (which not even you know) and make my browser send it with my requests, which is not easy even for the most astute hacker. The only way would be for me to operate in your computer after you logged in and before you logged out or your session token expires (usually a few minutes). Now, this is finally better (BTW I recommend you always explicitly log out instead of simply close the browser).

That session token that the server generates and your browser stores and resends - that is our little sweet cookie.

A Usage Example

Let’s pretend you are developing a web portal with sensible information that must be shielded behind an identity policy. You are willing to delegate the management if the identity policy to a specialized provider, who gives you peace of mind and saves you to develop your own user protection layer. Okta is such a provider. Our scenario is made of three entities

- Your application (APP), served by the app.com domain

- The application user (USER)

- The security provider (OKTA), served by the okta.com domain

Let’s drill down into a simple operation flow

- USER browses into a protected page in APP

- APP receives this first request but it doesn’t know USER yet

- APP asks identity info to OKTA

- OKTA displays the login page

- USER enters her credentials and logs in

- OKTA verifies the credentials and gives back to APP an identity token with an expiration time of 5 minutes

- APP is happy and returns to the browser the desired page

- After 5 minutes the identity token expires

- APP asks identity info to OKTA

- Go to step 4

Will USER be happy to repeat the login every 5 minutes? Probably not.

That’s why in step 6 OKTA adds a refresh-token cookie to its answer. So how does this make the flow different?

- USER browses into a protected page in APP

- APP receives this first request but it doesn’t know USER yet

- APP asks identity info to OKTA

- OKTA displays the login page

- USER enters her credentials and logs in

- OKTA verifies the credentials and gives back to APP an identity token with an expiration time 5 minutes AND a refresh-token cookie

- APP is happy and returns to the browser the desired page

- After 5 minutes the identity token expires

- APP asks identity info to OKTA

- OKTA receives the refresh-token cookie, and after verifying it, responds directly a new identity token, without login

- Go to step 7

The Same Site Policy

One important feature of cookies is that they are domain-aware. What this means is that the browser adds them to a request only when that request is bound to the same domain which initially sent the cookie back. In other words, the refresh-token will be sent from the browser only in requests to okta.com, not other domains.

In step 3, USER is happily surfing APP (.app.com) and a request is sent to Okta (.okta.com). The refresh-token hasn’t been created yet, so USER is presented with the Okta login page. In step 6 a refresh-token is returned from Okta (.okta.com), so the token is associated with the domain okta.com.

From now up to step 9, all requests are sent to app.com, so the refresh-token is not sent. But in step 9 the request goes to okta.com, so the refresh-token is sent through. Notice, though, that the browser is still showing a page served by APP, from the app.com domain. This is what is normally called a cross-site-request (CSR).

Cross-Site Request and the Forgery Danger

CSRs are an important feature that makes users experience better, but are open to misuse in a kind of cyber attack called cross-site-request-forgery (CSRF).

Malicious websites could, in fact, issue a request to a third-party website. As an example:

- You browse www.foo.com, which uses a back-end service at api.foo.com. Some cookies get stored locally, associated with the foo.com domain

- Then you move to www.baz.com, which issues a AJAX/Fetch (no change of page) request to api.foo.com. The browser takes all the cookies associated to foo.com and sends them through. If api.foo.com relies only on cookies to determine the legitimacy of the request, it will answer as though the request came from www.foo.com, and this is clearly a security breach. Note that the user in front of the computer wouldn’t be aware of this, since it occurs behind the scenes.

The SameSite Cookie’s Attribute

For this reason, changes have been introduced on how the browsers manage cookies in CSR scenarios. Long story short, we can today summarize three scenarios

A) Pre 2016. This is the legacy scenario, where browsers always send cookies for a domain whenever a request is made to that domain (as above)

B) After 2016 up to 2019/20. A new feature is introduced for cookies. When issuing a cookie, servers can mark it with a SameSite attribute. SameSite has two possible valid values: Lax and Strict. There are then 3 different possible behaviors for web browsers:

| SameSite Value | SameSite Behavior | Browser sends Cookies |

|---|---|---|

| Unspecified or Wrong | None | Always (as scenario A) |

| Lax | Lax | Last navigation action is to the cookie domain |

| Strict | Strict | Current content is from the cookie domain |

With this, foo.com can mark the refresh-token cookie as SameSite=Lax, and no cookie will be sent to api.foo.com for requests from baz.com or other domains different from foo.com.

This is an opt-in non-breaking feature. If websites don’t change anything, they still work as before (SameSite unspecified => legacy behavior). And this is what most of them chose to do, actually.

C) Latest (Chrome). To push the adoption of the SameSite feature as a new anti-CSRF measure, Google decided to change how Chrome works (from version 80), announcing the Incrementally Better Cookies initiative.

Now a new, valid value has been added to SameSite:

None.

Changes are as follows:

| SameSite Value | SameSite Behavior | Browser sends Cookies |

|---|---|---|

| Unspecified or Wrong | Lax | Last navigation action is to the cookie domain |

| Lax | Lax | Last navigation action is to the cookie domain |

| Strict | Strict | Current content is from the cookie domain |

| None | None | Always (as scenario A) |

This is an opt-out breaking change. The default behavior is not None (legacy), but Lax. Which means that application relying on cookies being always sent do not work any longer, forcing their owners to establish and implement a SameSite policy.

The Same Site Issue

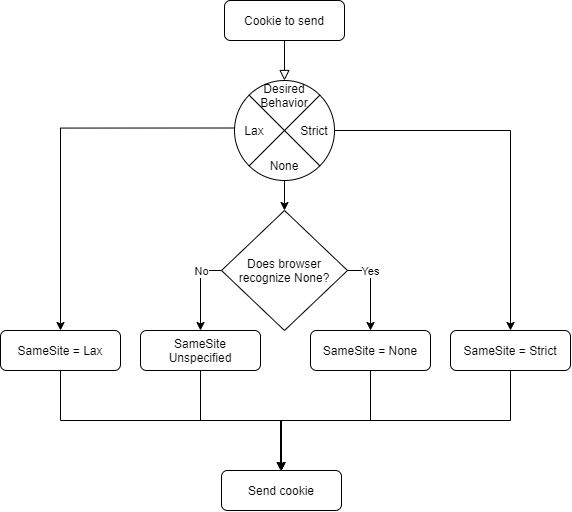

Unfortunately, this is not the only consequence of this choice made by Google. Earlier (but still in use) versions of Safari are affected by a bug (which won’t be fixed). They implement the first specifications for SameSite (B), but in case of wrong value for the SameSite attribute, they fall back to Strict instead of None. And, as in B None is not part of valid values for SameSite, these browser takes it as wrong, falling back to Strict. Do you see the problem? To restore your web site to the pre-SameSite functionality

- If the browser is Chrome, you need to set SameSite = None

- if the browser is in a range of Safari versions, you need to remove the SameSite = None and let it unspecified, otherwise, you get SameSite = Strict

The following table shows how different browsers operate with the SameSite attribute.

| Browser / SameSite Value | Unspecified | None | Lax | Strict |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chrome >= 51 | None | Ignored | Lax | Strict |

| Chrome >= 67 | None | None | Lax | Strict |

| Chrome >= 80 | Lax | None | Lax | Strict |

| Safari >= 12 | None | Wrong => Strict | Lax | Strict |

| Safari >= 13 | None | None | Lax | Strict |

| Firefox >= 60 | None | None | Lax | Strict |

| IE >= 11 | None | None | Lax | Strict |

| Edge >= 16 | None | None | Lax | Strict |

How to Fix the Same Site Issue

Fixing the Same Site issue requires additional logic in web servers, where the requesting browser is detected and becomes part of the calculation of the correct value for the cookies’ SameSite attribute.

Detecting the requesting browser type goes under the nomenclature of user-agent-sniffing. Among the wealthy amount of handshake information included in the HTTP protocol, we find a header named User-Agent. This is a string whose format is not standardized, therefore some attention must be paid when interpreting the value. Fortunately, it seems that the community has distilled an accepted pattern. There are three groups of user agents that need SameSite non-specified when the desired behavior is None:

- User-Agent contains “CPU iPhone OS 12” or “iPad; CPU OS 12” => iPhone, iPod Touch, iPad with iOS 12

- User-Agent contains “Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_14”, “Version/”, or “Safari” => Mac OS X Safari

- User-Agent contains “Chrome/5” or “Chrome/6” => Chrome 50-69 and pre-Chromium Edge

Example of ASP.NET Core C# Implementation

As an example, for an ASP.NET Core (including pre 3.1 versions), the code to be included in your application could be the following.

- An extension method for the Service Collection (ConfigureNonBreakingSameSiteCookies in the following snippet)

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Builder;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Http;

namespace Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection

{

public static class SameSiteCookiesServiceCollectionExtensions

{

/// <summary>

/// -1 defines the unspecified value, which tells ASPNET Core to NOT

/// send the SameSite attribute. With ASPNET Core 3.1 the

/// <seealso cref="SameSiteMode" /> enum will have a definition for

/// Unspecified.

/// </summary>

private const SameSiteMode Unspecified = (SameSiteMode) (-1);

/// <summary>

/// Configures a cookie policy to properly set the SameSite attribute

/// for Browsers that handle unknown values as Strict. Ensure that you

/// add the <seealso cref="Microsoft.AspNetCore.CookiePolicy.CookiePolicyMiddleware" />

/// into the pipeline before sending any cookies!

/// </summary>

/// <remarks>

/// Minimum ASPNET Core Version required for this code:

/// - 2.1.14

/// - 2.2.8

/// - 3.0.1

/// - 3.1.0-preview1

/// Starting with version 80 of Chrome (to be released in February 2020)

/// cookies with NO SameSite attribute are treated as SameSite=Lax.

/// In order to always get the cookies to send they need to be set to

/// SameSite=None. But since the current standard only defines Lax and

/// Strict as valid values there are some browsers that treat invalid

/// values as SameSite=Strict. We, therefore, need to check the browser

/// and either send SameSite=None or prevent the sending of SameSite=None.

/// Relevant links:

/// - https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-west-first-party-cookies-07#section-4.1

/// - https://tools.ietf.org/html/draft-west-cookie-incrementalism-00

/// - https://www.chromium.org/updates/same-site

/// - https://devblogs.microsoft.com/aspnet/upcoming-samesite-cookie-changes-in-asp-net-and-asp-net-core/

/// - https://bugs.webkit.org/show_bug.cgi?id=198181

/// </remarks>

/// <param name="services">The service collection to register <see cref="CookiePolicyOptions" /> into.</param>

/// <returns>The modified <see cref="IServiceCollection" />.</returns>

public static IServiceCollection ConfigureNonBreakingSameSiteCookies(this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.Configure<CookiePolicyOptions>(options =>

{

options.MinimumSameSitePolicy = Unspecified;

options.OnAppendCookie = cookieContext =>

CheckSameSite(cookieContext.Context, cookieContext.CookieOptions);

options.OnDeleteCookie = cookieContext =>

CheckSameSite(cookieContext.Context, cookieContext.CookieOptions);

});

return services;

}

private static void CheckSameSite(HttpContext httpContext, CookieOptions options)

{

if (options.SameSite == SameSiteMode.None)

{

var userAgent = httpContext.Request.Headers["User-Agent"].ToString();

if (DisallowsSameSiteNone(userAgent))

{

options.SameSite = Unspecified;

}

}

}

/// <summary>

/// Checks if the UserAgent is known to interpret an unknown value as Strict.

/// For those the <see cref="CookieOptions.SameSite" /> property should be

/// set to <see cref="Unspecified" />.

/// </summary>

/// <remarks>

/// This code is taken from Microsoft:

/// https://devblogs.microsoft.com/aspnet/upcoming-samesite-cookie-changes-in-asp-net-and-asp-net-core/

/// </remarks>

/// <param name="userAgent">The user agent string to check.</param>

/// <returns>Whether the specified user agent (browser) accepts SameSite=None or not.</returns>

private static bool DisallowsSameSiteNone(string userAgent)

{

// Cover all iOS-based browsers here. This includes:

// - Safari on iOS 12 for iPhone, iPod Touch, iPad

// - WkWebview on iOS 12 for iPhone, iPod Touch, iPad

// - Chrome on iOS 12 for iPhone, iPod Touch, iPad

// All of which are broken by SameSite=None, because they use the

// iOS networking stack.

// Notes from Thinktecture:

// Regarding https://caniuse.com/#search=samesite iOS versions lower

// than 12 are not supporting SameSite at all. Starting with version 13

// unknown values are NOT treated as strict anymore. Therefore we only

// need to check version 12.

if (userAgent.Contains("CPU iPhone OS 12")

|| userAgent.Contains("iPad; CPU OS 12"))

{

return true;

}

// Cover Mac OS X based browsers that use the Mac OS networking stack.

// This includes:

// - Safari on Mac OS X.

// This does not include:

// - Chrome on Mac OS X

// because they do not use the Mac OS networking stack.

// Notes from Thinktecture:

// Regarding https://caniuse.com/#search=samesite MacOS X versions lower

// than 10.14 are not supporting SameSite at all. Starting with version

// 10.15 unknown values are NOT treated as strict anymore. Therefore we

// only need to check version 10.14.

if (userAgent.Contains("Safari")

&& userAgent.Contains("Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10_14")

&& userAgent.Contains("Version/"))

{

return true;

}

// Cover Chrome 50-69, because some versions are broken by SameSite=None

// and none in this range require it.

// Note: this covers some pre-Chromium Edge versions,

// but pre-Chromium Edge does not require SameSite=None.

// Notes from Thinktecture:

// We can not validate this assumption, but we trust Microsofts

// evaluation. And overall not sending a SameSite value equals to the same

// behavior as SameSite=None for these old versions anyways.

if (userAgent.Contains("Chrome/5") || userAgent.Contains("Chrome/6"))

{

return true;

}

return false;

}

}

}

- The inclusion of a couple of required calls in the Startup code:

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

// Add this

services.ConfigureNonBreakingSameSiteCookies();

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app)

{

// Add this before any other middleware that might write cookies

app.UseCookiePolicy();

// This will write cookies, so make sure it's after the cookie policy

app.UseAuthentication();

}

Recap

In this article, I presented the Same Site cookie feature, the issues introduced for web application providers, and the way to fix those issues.

Now you can apply these changes to your .NET app, and use your Okta account to handle all the rest of the user security work!

What you learned:

- What is a cookie and how it works

- What is a Cross-Site Request (CSR) and how it can be misused to launch Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) attacks

- What is the SameSite cookie’s attribute and why it was introduced

- How the Same Site feature changed in response to a poor server-side adoption

- How the Same Site Issue was generated, and why it requires web app owner to implement changes in their codebase

- A simple workflow to implement in a web server in order to make it healthy regardless of different browsers Same Site behavioral nuances

- A community tested-and-accepted code implementation of the workflow for ASP.NET Core using C#

Learn More About Okta and .NET Security

If you are interested in learning more about security and the Same Site feature and issue, check out these other blog posts!

- Secure Your ASP.NET Core App with OAuth 2.0

- Build Single Sign-on for Your ASP.NET MVC App

- Policy-Based Authorization in ASP.NET Core

- Okta ASP.NET Core MVC Quickstart

Make sure to follow us on Twitter, subscribe to our YouTube Channel and check out our Twitch channel so that you never miss any awesome content!

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.