Make Java Tests Groovy With Hamcrest

My favorite way to test Java code is with Groovy. Specifically, writing tests in Groovy with Hamcrest. In this post, I’ll walk through how to test a simple Spring Boot application with these tools.

Groovy is an optionally typed dynamic language for the JVM, and can be compiled statically. That is a mouthful and I’ll explain this as we go, but for now think of Groovy as Java with lots of sugar.

Groovy is a great language for writing tests because it is close enough to the Java syntax that your typical Java developer can pick it up right away (unlike other JVM languages). It is MUCH less verbose then it’s older cousin, you can access private and protected elements from your tests (more on that below), and the sugar!

Note: In May 2025, the Okta Integrator Free Plan replaced Okta Developer Edition Accounts, and the Okta CLI was deprecated.

We preserved this post for reference, but the instructions no longer work exactly as written. Replace the Okta CLI commands by manually configuring Okta following the instructions in our Developer Documentation.

Pour Some Sugar On Me

Syntactic sugar is syntax that makes code easier to read and comprehend; and Groovy is sweet! Writing clear, succinct code saves time when writing tests and doubly so when maintaining them.

With Groovy, defining lists and maps become trivial:

def myMap = [key1: "value1",

key2: "value2",

nested: [

anotherKey: "anotherValue"

]]

def myList = ["one", "two", "three"]

The Elvis operator makes ternary expressions shorter:

def displayName = user.name ?: 'Anonymous'

String interpolation! Seriously, why do we not have this not in Java yet?

def answer = 42

println "The answer to the ultimate question of life, " +

"the universe and everything is ${answer}"

Results in:

The answer to the ultimate question of life, the universe and everything is 42

Groovy has support for default method parameter values, and while you can accomplish the same thing in Java, it is more verbose. For example, in Groovy we could write:

String sayHello(String name = "Joe", String greeting = "How are you?") {

println "Hello ${name}, ${greeting}"

}

The Java equivalent would be:

public String sayHello() {

return sayHello("Joe");

}

public String sayHello(String name) {

return sayHello(name, "How are you?");

}

public String sayHello(String name, String greeting) {

System.out.println("Hello " + name + ", " greeting);

}

The Groovy block is faster to write and more concise.

Optional Typing In Groovy

When defining variables in Groovy the type definition is optional. Using the def keyword is a shorthand for defining a type as Object. This, combined with Groovy’s duck typing means writing less code.

Optional typing is a topic I want to clarify, especially if you use the var keyword added in Java 10. With Java, the type associated with var is resolved from the variable initializer, so something like this would fail to compile because the resolved type is a String:

var foo = "bar";

foo = 5;

The type of a def is dynamic so the following Groovy is perfectly valid:

def foo = "bar"

foo = 5

I’m NOT saying you should mix integers and strings, but this is useful in other scenarios when you want to make use of duck typing.

Clone the Test Application

I’m going to start with an existing application and add then add tests. Yes, I know, bad developer, we should all be writing tests first.

Clone the repo:

git clone https://github.com/oktadeveloper/java-test-groovy-example

cd java-test-groovy-example

If you want to skip to the end and just see the code and tests take a look at the with-tests branch.

Configure Groovy Maven

To add support for Groovy in a Maven project, I use the GMavenPlus plugin. This plugin will compile our Groovy test classes. It could also handle your regular (non-test) code as well, but today, I just need to compile tests.

In the plugins section of the pom.xml file just add:

<plugin>

<groupId>org.codehaus.gmavenplus</groupId>

<artifactId>gmavenplus-plugin</artifactId>

<version>1.7.1</version>

<dependencies>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.codehaus.groovy</groupId>

<artifactId>groovy</artifactId>

<version>${groovy.version}</version>

</dependency>

</dependencies>

<executions>

<execution>

<goals>

<!-- This goal adds Groovy test sources to the project's test sources. -->

<goal>addTestSources</goal>

<goal>compileTests</goal> <!-- Compiles tests -->

<!-- generates stubs in target/generated-sources/groovy-stubs/test, only needed when

compiling Java code that depends on Groovy code -->

<goal>generateTestStubs</goal>

<goal>removeTestStubs</goal> <!-- remove generated stubs from sources list -->

</goals>

</execution>

</executions>

</plugin>

I’ve also defined the property: groovy.version in the <properties> section of the pom.xml:

<properties>

<groovy.version>2.5.8</groovy.version>

</properties>

Add Dependencies for Groovy, Hamcrest and TestNG

Lastly, we just need to add a few dependencies Groovy, Hamcrest, and TestNG (you could use JUnit instead, if that is more your style).

<dependency>

<groupId>org.codehaus.groovy</groupId>

<artifactId>groovy</artifactId>

<version>${groovy.version}</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.hamcrest</groupId>

<artifactId>hamcrest</artifactId>

<version>2.1</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

<dependency>

<groupId>org.testng</groupId>

<artifactId>testng</artifactId>

<version>6.14.3</version>

<scope>test</scope>

</dependency>

NOTE: It may seem a bit funny that the groovy dependency is defined both in the dependencies section and the plugin section. This has to do with how plugins are loaded in Maven. Just keep the two the same and everything will work out.

Write A Test

This simple Spring Boot application only has one class:

package com.okta.example.groovytesting;

import org.springframework.boot.SpringApplication;

import org.springframework.boot.autoconfigure.SpringBootApplication;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.GetMapping;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RequestParam;

import org.springframework.web.bind.annotation.RestController;

import java.util.Objects;

@SpringBootApplication

@RestController

public class SimpleApplication {

public static void main(String[] args) {

SpringApplication.run(SimpleApplication.class, args);

}

@GetMapping("/")

private String welcome() {

return "Hello";

}

@GetMapping("/add")

public int add(@RequestParam("a") int a, @RequestParam("b") int b) {

return a + b;

}

@GetMapping("/concat")

public String concat(@RequestParam("a") String a, @RequestParam("b") String b) {

return Objects.toString(a, "") + Objects.toString(b, "");

}

}

So far, so good. We haven’t ventured outside of a normal Java application. Time to get Groovy!

Add a new file: src/test/groovy/com/okta/example/groovytesting/SimpleApplicationTest.groovy, that may seem like a mouthful, but if you replace the first and last groovy with java it would be business as usual.

package com.okta.example.groovytesting

import org.testng.annotations.Test

import static org.hamcrest.MatcherAssert.assertThat

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.allOf

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.containsString

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.greaterThan

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.is

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.emptyString

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.lessThan

class SimpleApplicationTest {

}

In this class I’ll add a few test methods. Of note above you will see the only TestNG reference is the @Test annotation. If you wanted to use JUnit instead you could just swap Test annotations because Hamcrest handles all of the assertions directly.

Using Hamcrest

A while ago, I found myself writing a bunch of repetitive tests that looked like this:

Assert.assertEquals(actual, expected, "my terrible error message")

Assert.assertTrue(1 == 1, "Likely omitted error message")

Enter Hamcrest, a declarative matcher library typically used for testing. Hamcrest makes your tests more by replacing assertion logic with simple matchers expressions. Hamcrest is all about Matchers, so much so that “Hamcrest” is actually an anagram for “Matcher”.

A Hamcrest Matcher has two methods:

boolean matches(Object actualValue)- Think of this as a replacement usingassertTruedescribeMismatch(Object actual, Description mismatchDescription)- Adds a useful description in the case of a mismatch

Most of the time you will use one of the many Matchers, Hamcrest provides out of the box, typically used with static imports:

import static org.hamcrest.MatcherAssert.assertThat

import static org.hamcrest.Matchers.*

// ...

assertThat "foobar", containsString("foo")

The default error message is pretty good too, for example, the obviously broken test:

assertThat 1 + 1, is(3)

Results in with the following error:

java.lang.AssertionError:

Expected: is <3>

but: was <2>

The error message for more complex matchers is better, for example, if I were to write:

assertThat "bar", containsString("foo")

The error message would be:

java.lang.AssertionError:

Expected: a string containing "foo"

but: was "bar"

Expected :foo

Actual :bar

Test a Private Method with Groovy

Yes, I’m calling a private method. Now, I know many of you will find this appalling, others have closed their browser tab at the first mention of this. This is one of those “with great power, comes great responsibility” things. Have you ever needed to extract some complex logic out into a private method? Ever needed to test it? This also works with protected methods, if that makes you feel better.

@Test

void welcomeTest() {

def app = new SimpleApplication()

// welcome() is private

assertThat app.welcome(), is("Hello")

}

The Java-based alternative would use either using reflection or weakening the scope of the actual method to package-private, or publicly accessible with public or protected, which typically means adding documentation (that nobody will read).

Ever seen anything like:

/**

* This method is exposed for testing only, it may change in the future without notice.

**/

@VisibleForTesting

public Object iWishThisWasPrivate() {

// ...

}

I think it’s better to avoid this scenario entirely when possible.

Add OAuth 2.0 Support to the Application

Now that we have tested our application, we can go ahead and start it.

Before you begin, you’ll need a free Okta developer account. Install the Okta CLI and run okta register to sign up for a new account. If you already have an account, run okta login.

Then, run okta apps create. Select the default app name, or change it as you see fit.

Choose Web and press Enter.

Select Okta Spring Boot Starter.

Accept the default Redirect URI values provided for you. That is, a Login Redirect of http://localhost:8080/login/oauth2/code/okta and a Logout Redirect of http://localhost:8080.

What does the Okta CLI do?

The Okta CLI will create an OIDC Web App in your Okta Org. It will add the redirect URIs you specified and grant access to the Everyone group. You will see output like the following when it’s finished:

Okta application configuration has been written to:

/path/to/app/src/main/resources/application.properties

Open src/main/resources/application.properties to see the issuer and credentials for your app.

okta.oauth2.issuer=https://dev-133337.okta.com/oauth2/default

okta.oauth2.client-id=0oab8eb55Kb9jdMIr5d6

okta.oauth2.client-secret=NEVER-SHOW-SECRETS

NOTE: You can also use the Okta Admin Console to create your app. See Create a Spring Boot App for more information.

Make sure your Okta app’s values are in src/main/resources/application.properties.

okta.oauth2.issuer=https://{yourOktaDomain}/oauth2/default

okta.oauth2.client-id={yourClientId}

okta.oauth2.client-secret={yourClientSecret}

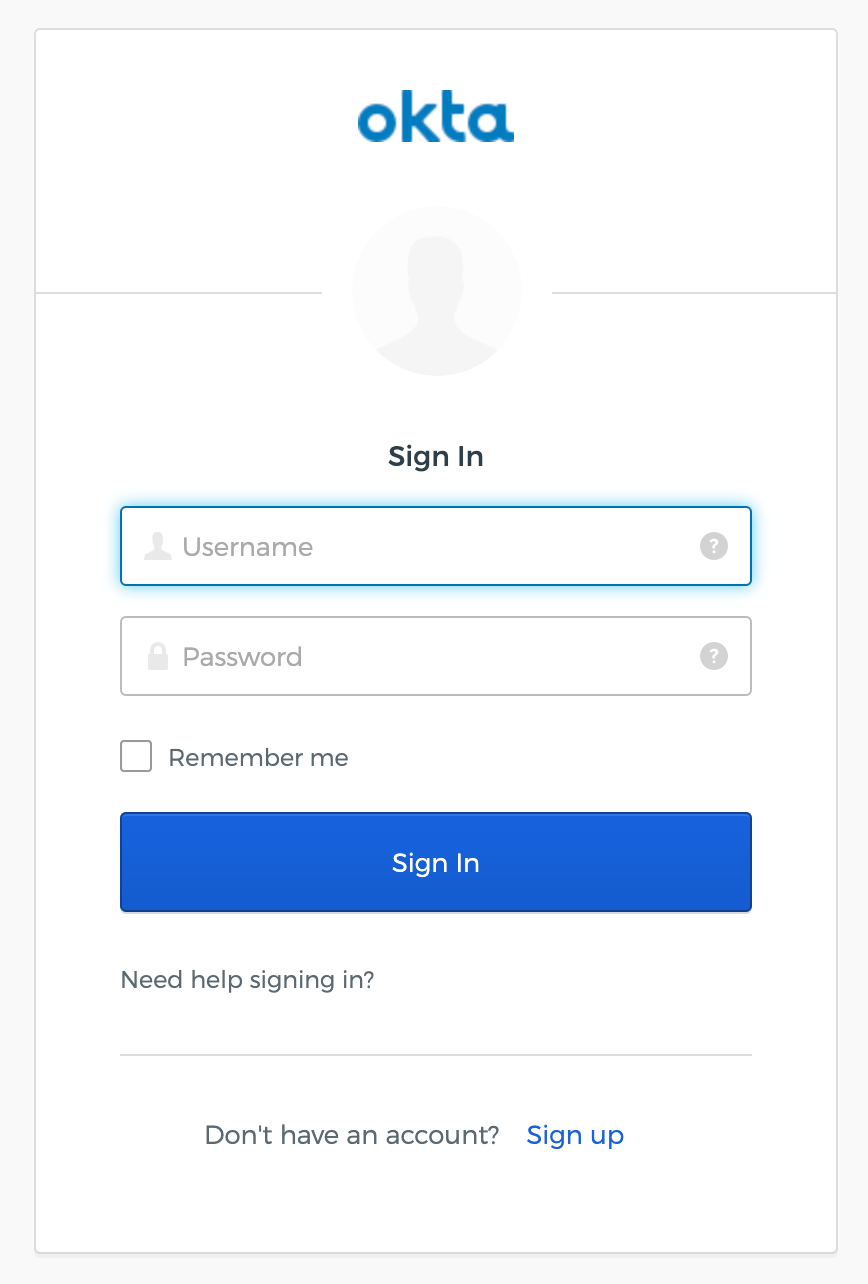

Simply run ./mvnw, open a new Incognito window and browse to http://localhost:8080/. You will be prompted to log in – use your new Okta credentials.

Just those three properties are all it takes to secure your application with Okta and OAuth 2.0/OIDC.

It’s Been Groovy

In this post, I’ve written a few simple tests with Groovy and Hamcrest. The Groovy documentation site is a great place to learn more. If you are new to Hamcrest you should also check out Spotify Hamcrest which provides a bunch of useful matchers on top of the base library.

If you want to learn more about Okta follow us on Twitter @OktaDev, the OktaDev YouTube channel, or these posts:

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.