Protect Your Angular App From Cross-Site Scripting

In the last post of this SPA security series, we covered Cross-Site Request Forgery (CSRF) and how Angular helps you with a mitigation technique.

| Posts in the SPA web security series |

|---|

| 1. Defend Your SPA From Security Woes |

| 2. Defend Your SPA From Common Web Attacks |

| 3. Protect Your Angular App From Cross-Site Request Forgery |

| 4. Protect Your Angular App From Cross-Site Scripting |

Next, we’ll dive into Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) and look at the built-in security guards you get when using Angular.

Table of Contents

- Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) protection

- XSS support in Angular

- Angular automatically escapes values

- Angular automatically sanitizes values

- Bypassing Angular’s security checks

- Use ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation for extra security

- Don’t concatenate strings to construct templates

- Beware of constructing DOM elements without using Angular templates

- Explicitly sanitize data

- Consider Trusted Types

- Learn more about XSS, Trusted Types, and creating applications using Angular

Cross-Site Scripting (XSS) protection

In the second post of this series, we presented an overview of Cross-Site Scripting (XSS). In summary, you learned that XSS occurs when code pollutes data and your application doesn’t provide safeguards to prevent the code from running.

Let’s recap the example attack vector.

Imagine an overly dramatic but otherwise innocent scenario like this:

- A website allows you to add comments about your favorite K-Drama.

- An agitator adds the comment

<script>alert('Crash Landing on You stinks!');</script>.- That terrible comment saves as is to the database.

- A K-Drama fan opens the website.

- The terrible comment is added to the website, appending the

<script></script>tag to the DOM.- The K-Drama fan is outraged by the JavaScript alert saying their favorite K-Drama, Crash Landing on You, stinks.

In this example, we have a <script> element and glossed over the steps for appending the element to the DOM. In reality, polluted data gets pulled into the application in various ways. Adding untrusted data in an injection sink - a Web API function that allows us to add dynamic content to our applications - is a major culprit. Examples of sinks include, but aren’t limited to:

- methods to append to the DOM such as

innerHTML,outerHTML - approaches that load external resources or navigate to external sites via a URL, such as

srcorhreffor HTML elements andurlproperty on styles - event handlers, such as

onmouseoverandonerrorwith an invalidsrcvalue - global functions that evaluate and/or run code, such as

eval(),setTimeout()

As you can see, there are many vectors for the vulnerability. Many of these sinks have legitimate use cases when building dynamic web applications. Since the sinks are necessary for web app functionality, we must use trusted data by escaping and sanitizing it.

This is still a high-level summary. The fine print is that XSS vulnerabilities can be pretty sneaky in the different ways the attack can occur.

There are different XSS attacks, each with a slightly different attack vector. We’ll briefly cover how three attacks work.

Stored XSS

In this flavor of XSS, the attack is persisted somewhere, like in a database. We recapped stored XSS in the example above, where an agitator’s terrible comment with the script tag persists in the database and ruins someone else’s day by showing the unfriendly comment in an alert.

Reflected XSS

In this attack, the malicious code sneaks in through the HTTP request, usually through URL parameters. Suppose the K-Drama site takes a search term via a URL parameter, such as:

https://myfavekdramas.com/dramas?search=crash+landing+on+you

The site then takes the search terms and displays them back to the user while calling out to the backend to run the search.

But what if an agitator constructs a URL like this?

https://myfavekdramas.com/dramas?search=<img src=1 onerror="alert('Doh!')"/>

You may think that you’d never navigate to a link like that! Who would?! But let’s remember, in a previous post, you did click the link in your spam email to send money to your high school sweetheart. This isn’t meant as a judgment; no one is immune to clicking fishy links. Also, agitators are pretty tricksy. They might use URL shorteners to obscure the risk.

DOM-based XSS

In this attack, the agitator takes advantage of Web APIs. The attack occurs entirely within the SPA, and it’s pretty much identical to reflected XSS.

Let’s say our application depends on an external resource—the app embeds an <iframe> for showing trailers for the K-Dramas and sets the iframe’s src attribute to an external site. So our code might look like this.

<iframe src="{resourceURL}" />

We usually call out to the third-party service to get the URLs for the source, but agitators have infiltrated this third-party service and now control the resource URLs returned, making our code look like this.

<iframe src="javascript:alert('Boo!')" />

Well, darn it, we’ve got some problems.

XSS support in Angular

Fortunately, Angular has a lot of built-in security protections. It treats all values as suspicious and untrusted by default, which is incredibly helpful because the framework automatically guards us against unintentionally creating vulnerabilities in our applications. Angular automatically removes any script tags so we won’t have to worry about the original hypothetical example.

Let’s see some examples of how Angular protects us against XSS.

Angular automatically escapes values

Web applications implement comment features like in the Stored XSS example by calling an API to get a list of comments, then add the comments to the template. In Angular, an extremely simplified comments component might look something like this:

@Component({

selector: 'app-comments'

template: `

<p *ngFor="let comment of comments | async">

{{comment}}

<p>

`

})

export class CommentsComponent implements OnInit {

public comments: Observable<string[]>;

constructor(private commentsService: CommentsService) { }

public ngOnInit(): void {

this.comments = this.commentsService.getComments();

}

}

The XSS attack vector works only if the web app treats all values as trustworthy and appends them directly to the template, such as when the web app doesn’t escape or sanitize values first. Luckily, Angular automatically does both.

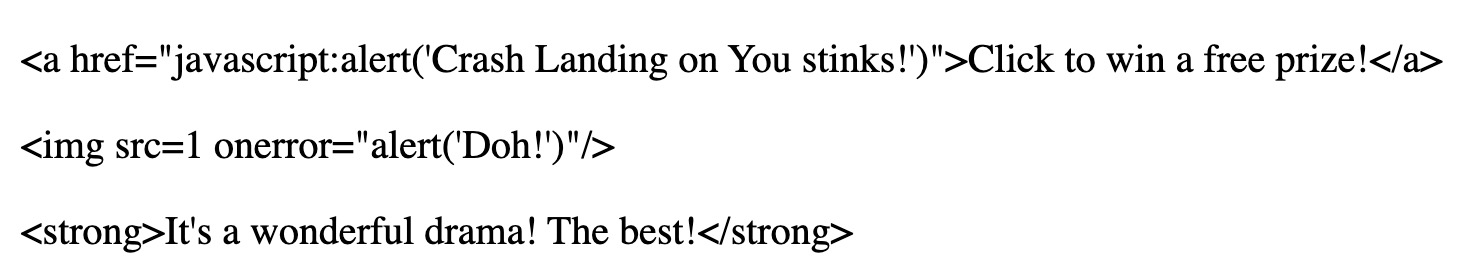

When you add values through interpolation in templates (using the {{}} syntax), Angular automatically escapes the data. So the comment:

<a href="javascript:alert(\'Crash Landing on You stinks!\')">Click to win a free prize!</a>

displays exactly like what’s written above as text. It’s still a terrible comment and unfriendly to “Crash Landing on You” fans, but it doesn’t add the anchor element to the app. This is awesome because even if the attack were more malicious, it still wouldn’t perform any actions.

Angular automatically sanitizes values

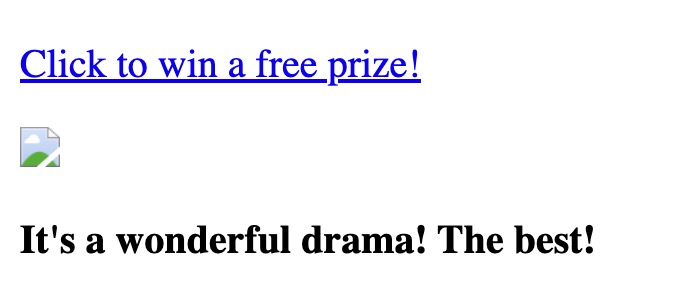

Let’s say we want to display the comments preserving any safe markup a user enters. We already have two malicious comments to start us off on shaky ground:

<a href="javascript:alert(\'Crash Landing on You stinks!\')">Click to win a free prize!</a><img src=1 onerror="alert('Doh!')"/>

Then a K-Drama fan adds a new comment with safe markup.

<strong>It's a wonderful drama! The best!</strong>

Because the CommentsComponent uses interpolation to populate the comments, the comments will display in the browser in text like this:

That’s not what we want! We want to interpret the HTML and allow the <strong> text, so we change our component template to bind it to the HTML innerHTML property.

<p

*ngFor="let comment of comments | async"

[innerHTML]="comment"

>

<p>

Now, the site displays only the second comment correctly formatted like this:

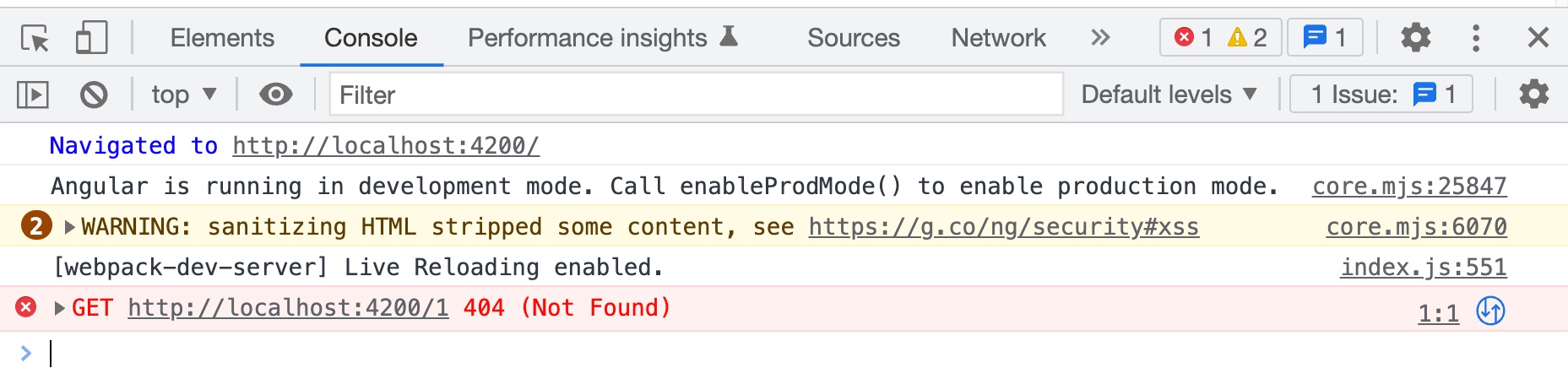

The first comment with the anchor tag doesn’t display the alert when clicked! The second comment with the attack in the onerror handler only shows the broken image and doesn’t run the error code! Angular doesn’t publish a list of unsafe tags. Still, we can sneak a peek into the codebase to see Angular considers tags such as form, textarea, button, embed, link, style, template as suspicious and may altogether remove the tag or remove specific attributes/child elements.

As we learned earlier, sanitizing removes suspicious code while keeping safe code. Angular automatically strips out unsafe attributes from safe elements. You will see a warning in the console letting you know Angular cleaned the content up.

By handling values “the Angular way,” our application is well protected against security woes! Success!

Bypassing Angular’s security checks

🚨 Here be dragons! 🚨

Be careful about bypassing the built-in security mechanism; if you need to, read this section carefully:

What if you need to bind trusted values that Angular thinks are unsafe? You can mark values as trusted and bypass the security checks.

Let’s look at the example of the image with an error handler. Instead of the value coming from an agitator, let’s say there’s a legitimate need to bind the image with dynamic error handling.

Sidenote - there are better ways to handle images with error handling in Angular if your application doesn’t need to be quite so dynamic. Consider using an image element and bind to

(error)instead, or evenHostListener. Or, there are many tutorial examples of handling it cleanly using a Directive. Indeed, there are lots of better options. You should always prefer the standard Angular way using Angular building blocks. The code will be way easier to support.

Back to the example, then. In the example above, we saw that the error handler didn’t run. Angular stripped it out. We need to mark the code as trusted for the error code to run.

Your component code might look like this.

@Component({

selector: 'app-trustworthy-image',

template: `

<section [innerHTML]="html"

`

})

export class TrustworthyImageComponent {

public html = `<img src=1 onerror="alert('Doh!')"/>`;

}

You see the broken image in the browser, and no alert pops up.

We can use the DomSanitzer class in @angular/platform-browser, to mark values as safe. The DomSanitizer class has built-in sanitization methods for four types of contexts:

- HTML - binding to add more content like this

innerHTMLimage example - Style - binding styles to add more flair to the site

- URL - binding URLs like when you want to navigate to an external site in an anchor tag

- Resource URL - binding URLs that load and run as code

To mark the value as trusted and safe to use, you can inject DomSanitizer and use one of the following methods appropriate for the security context to return a value marked as safe.

bypassSecurityHTMLbypassSecurityScriptbypassSecurityTrustStylebypassSecurityTrustUrlbypassSecurityTrustResourceUrl

These methods return the same input but are marked as trusted by wrapping it in a safe equivalent of the sanitization type.

Let’s see what this component looks like when we mark the HTML value as trusted.

@Component({

selector: 'app-trustworthy-image',

template: `

<section [innerHTML]="html"

`

})

export class TrustworthyImageComponent {

public html = `<img src=1 onerror="alert('Doh!')"/>`;

public safeHtml: SafeHtml;

constructor(sanitizer: DomSanitizer) {

this.safeHtml = sanitizer.bypassSecurityTrustHtml(this.html);

}

}

Now, if you view this in the browser, you’ll see the broken image and an alert pop up. Success?? Maybe…

Let’s look at an example with a resource URL, such as the DOM-based XSS example where we bind the URL of the iframe source.

Your component code might look like this

@Component({

selector: 'app-video',

template: `

<iframe [src]="linky" width="800px" height="450px"

`

})

export class VideoComponent {

// pretend this is from an external source

public linky = '//videolink/embed/12345';

}

Angular will stop you right there. 🛑

You’ll see an error in the console saying unsafe values can’t be used in a resource URL. Angular recognizes you’re trying to add a resource URL and is alarmed you’re doing something dangerous. Resource URLs can contain legitimate code, so Angular can’t sanitize it, unlike the comments we had above.

If we are sure our link is safe and trustworthy (highly debatable in this example, but we’ll ignore that for a moment), we can mark the resource as trusted after we do some cleanup to make the resource URL safer.

Remember, we should only use the

bypassSecurityTrust...methods if we know the value is trustworthy. You bypass the built-in security mechanisms and open yourself to security vulnerabilities!

Instead of using the entire video URL based on the external party’s API response, we’ll construct the URL by defining the video host URL within our app and appending the video’s ID that we get back from the external party’s API response. This way, we aren’t entirely reliant on a potentially untrustworthy value from a third party. Instead, we’ll have some measure of ensuring we’re not injecting malicious code into the URL.

Then we’ll mark the video URL as trusted and bind it in the template. Your VideoComponent changes to this:

@Component({

selector: 'app-video',

template: `

<iframe [src]="safeLinky" width="800px" height="450px"

`

})

export class VideoComponent {

// pretend this is from an external source

public videoId = '12345';

public safeLinky!: SafeResourceUrl;

constructor(private sanitizer: DomSanitizer) {

this.safeLinky = sanitizer.bypassSecurityTrustResourceUrl(`//videolink/embed/${this.videoId}`)

}

}

Now you’ll be able to show trailers of the K-Dramas on your site in an iframe in a much safer way.

It can’t be stressed enough. Ensure you trust the values before bypassing the out-of-the-box security protections you get from Angular!

Great! So we’re done? Not quite. There are a couple of things to note.

Use ahead-of-time (AOT) compilation for extra security

Angular’s AOT compilation has extra security measures for injection attacks like XSS. AOT compilation is highly recommended for production code and has been the default compilation method since Angular v9. Not only is it more secure, but it also improves performance.

On the flip side, the other form of compilation is Just-in-time (JIT). JIT was the default for older versions of Angular. JIT compiles code for the browser on the fly, and this process skips Angular’s built-in security protection, so stick with using AOT.

Don’t concatenate strings to construct templates

Angular trusts template code and only escapes values defined in the template using interpolation. So if you attempt something clever to circumvent the more common forms of defining the template for a component, you won’t be protected.

For example, you won’t have Angular’s built-in protections if you try to dynamically construct templates combining HTML with data using string concatenation or have an API whip up a payload with a template you somehow inject into the app. Your clever hacks with dynamic components might cause you security woes.

Beware of constructing DOM elements without using Angular templates

Any funny business you might try using ElementRef or Renderer2 is the perfect way to cause security issues. For example, you can pwn yourself if you try to do something like this.

@Component({

selector: 'app-yikes',

template: `

<div #whydothis></div>

`

})

export class YikesComponent implements AfterViewInit {

@ViewChild('whydothis') public el!: ElementRef<HTMLElement>;

// pretend this is from an external source

public attack = '<img src=1 onerror="alert(\'YIKES!\')"';

constructor(private renderer: Renderer2) { }

public ngAfterViewInit(): void {

// danger below!

this.el.nativeElement.innerHTML = this.attack;

this.renderer.setProperty(this.el.nativeElement, 'innerHTML', this.attack);

}

}

Something like this might be tempting in a fancy custom directive, but think again! Besides, interacting directly with the DOM like this isn’t the best practice in Angular, even beyond any security issues it might have. It’s always wise to prefer creating and using Angular templates.

Explicitly sanitize data

The DomSanitizer class also has a method to sanitize values explicitly.

Let’s say you cook up a legitimate need to use ElementRef or Render2 to build out the DOM in code. You can sanitize the value you add to the DOM using the method sanitize(). The sanitize() method takes two parameters, the security context for the sanitization and the value. The security context is an enumeration matching the security context listed previously.

If we redo the YikesComponent to explicitly sanitize, the code looks like this.

@Component({

selector: 'app-way-better',

template: `

<div #waybetter></div>

`

})

export class WayBetterComponent implements AfterViewInit {

@ViewChild('waybetter') public el!: ElementRef<HTMLElement>;

// pretend this is from an external source

public attack = '<img src=1 onerror="alert(\'YIKES!\')"';

constructor(private renderer: Renderer2, private sanitizer: DomSanitizer) { }

public ngAfterViewInit(): void {

const cleaned = this.sanitizer.sanitize(SecurityContext.HTML, this.attack);

this.renderer.setProperty(this.el.nativeElement, 'innerHTML', cleaned);

}

}

Now you’ll have the image without the potentially dangerous code tagging along for the ride.

Consider Trusted Types

One more built-in security mechanism in Angular is setting up and using a Content Security Policy (CSP). CSPs are a specific HTTP security header we covered in the first post to help set up foundational security mechanisms.

Angular has built-in support for defining policies for a CSP called Trusted Types. Trusted Types are a great way to add extra XSS security guards to your Angular app but isn’t supported across all the major browsers yet. If you are interested in learning more about setting up the Trusted Types CSP for SPAs, check out this great post from the Auth0 blog - Securing SPAs with Trusted Types.

Learn more about XSS, Trusted Types, and creating applications using Angular

This series taught us about web security, common web attacks, and how Angular’s built-in security mechanisms protect us from accidental attacks.

| Posts in the SPA web security series |

|---|

| 1. Defend Your SPA From Security Woes |

| 2. Defend Your SPA From Common Web Attacks |

| 3. Protect Your Angular App From Cross-Site Request Forgery |

| 4. Protect Your Angular App From Cross-Site Scripting |

If you liked this post, you might be interested in these links.

- Security documentation from Angular

- How to Build Micro Frontends Using Module Federation in Angular

- Three Ways to Configure Modules in Your Angular App

- Defending against XSS with CSP

- Securing SPAs with Trusted Types

Don’t forget to follow us on Twitter and subscribe to our YouTube channel for more great tutorials. We’d also love to hear from you! Please comment below if you have any questions or want to share what tutorial you’d like to see next.

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.