The Identity of OAuth Public Clients

I recently got back from a series of events filled with lots of interesting discussions around various OAuth-related topics. At the official IETF meeting in Vienna back in March, I presented the latest work on OAuth 2.1 and we discussed and made progress on some of the current open issues. At the OAuth Security Workshop a few weeks later, I presented a session on client authentication for mobile apps, and there were many more presentations on a huge variety of topics. Many of us went straight from there to the European Identity and Cloud Conference to continue those discussions the next week.

One recurring theme that came up across the series of events concerned the idea of OAuth client impersonation and authentication.

What is OAuth client impersonation?

In short, OAuth client impersonation is when one OAuth client pretends to be another, usually to take advantage of any capabilities that the legitimate client may have that are not granted to other clients.

In OAuth terminology, a “Confidential Client” is an application that is issued credentials by the authorization server and can use these credentials to authenticate itself to the OAuth server when doing things like requesting access tokens. The credential can be a simple client secret or a more secure option such as a private key used to sign a JWT. The benefit of using client authentication of any sort, assuming the client properly protects its credentials, is that the OAuth server knows that any requests made with those credentials are from the legitimate client, and client impersonation isn’t possible.

On the other hand, a “Public Client” is an application that doesn’t have credentials, hence cannot prove its own identity when contacting the authorization server for tasks such as requesting access tokens. Usually this is because it would be impossible to deploy such an application with credentials in a way that would remain secret. Common examples of public clients are single-page apps and mobile/desktop apps. In both cases, if you were to try to include a client secret in the app, it would be possible for anyone to extract the secret, which means it would no longer be secret. For this reason, it has always been the case that OAuth flows for public clients are done with entirely public information.

Originally, the Implicit flow was recommended for both SPAs and mobile apps. Proof Key for Code Exchange (also known as PKCE) was later introduced as an additional security feature for the authorization code flow, primarily targeted at mobile apps. As browsers evolved, it eventually became possible to do the authorization code flow with PKCE from single-page apps as well. The current draft of the OAuth Security Best Current Practice deprecates the use of the Implicit flow, and recommends using PKCE for both SPAs and mobile apps, as well as web server applications. That said, this recommendation has nothing to do with client impersonation. PKCE solves a number of different attacks, and even solves attacks that are still possible with a client secret, but it is not a form of client authentication so it doesn’t solve client impersonation attacks for public clients.

For public clients, both the Implicit flow and Authorization Code flow with PKCE are done with only the publicly-known information about the client: the client_id and redirect_uri. Since there is no client authentication used, it is possible for anyone to take that information and pretend to be that client by doing an OAuth flow that looks identical to the real app.

Should I be worried about client impersonation?

Maybe and maybe not! Whether client impersonation can be used for any ill purpose depends on how you treat OAuth clients in your system. Many companies aren’t concerned with this problem at all. There are plenty of situations where being able to impersonate a client doesn’t actually benefit an attacker at all.

Let’s take a closer look at some of the things an attacker might be interested in doing if client impersonation is possible.

The authorization server is where all the decisions around issuing tokens are made, things like how long tokens should last and what claims should be added to a token. Sometimes these decisions involve policies that depend on the identity of the client application that will be receiving the access token. If an attacker impersonates a valid client, the authorization server would be using the policies of the valid client for the requests coming from the attacker’s client.

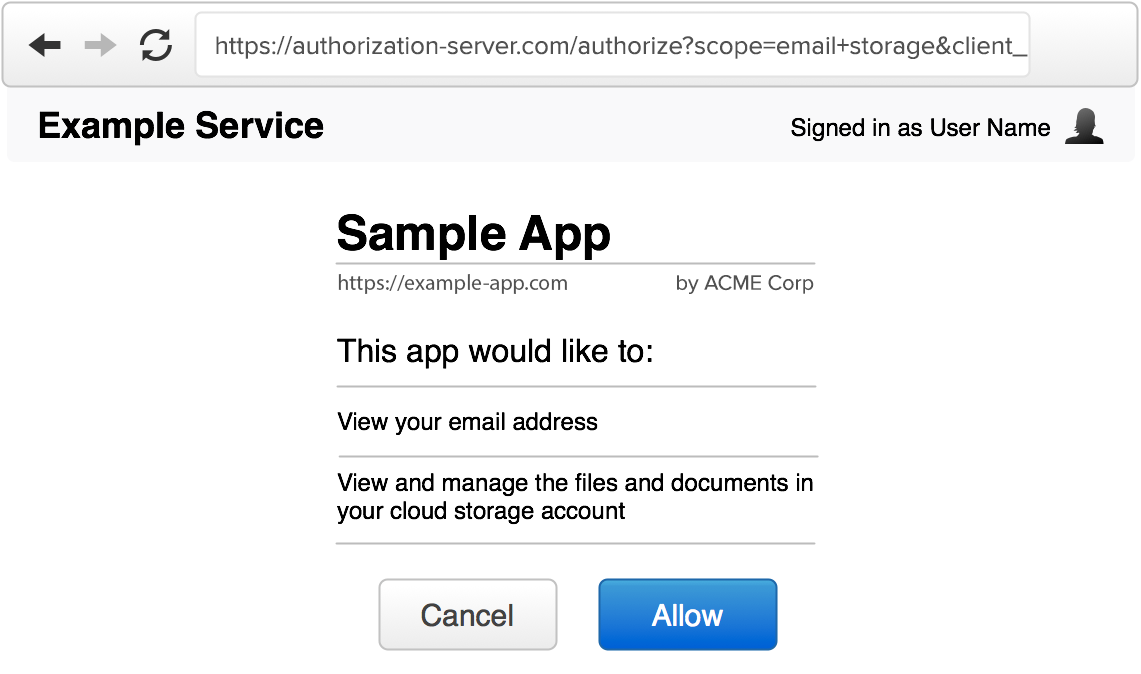

Bypassing the consent screen

One example is the decision of whether or not to show a consent screen to inform the user of which application they are logging in to. For third-party apps, the consent screen is a critical part of the flow, communicating which app is requesting access to the user’s account and what information will be shared with the app. For first-party apps, where the app is the same brand as the data being accessed, it doesn’t necessarily make sense to ask the user for this permission. It would be awkward, for example, if the Twitter app asked you for permission to access your Twitter data. For this reason, many companies want to bypass the consent screen for first-party apps. With this policy in place, and with public clients, impersonating a first-party app means bypassing the consent screen and immediately issuing tokens to the impersonating application.

This accomplishes basically nothing if you do this to your own account on your own device, but is potentially more interesting if you can accomplish this on someone else’s device.

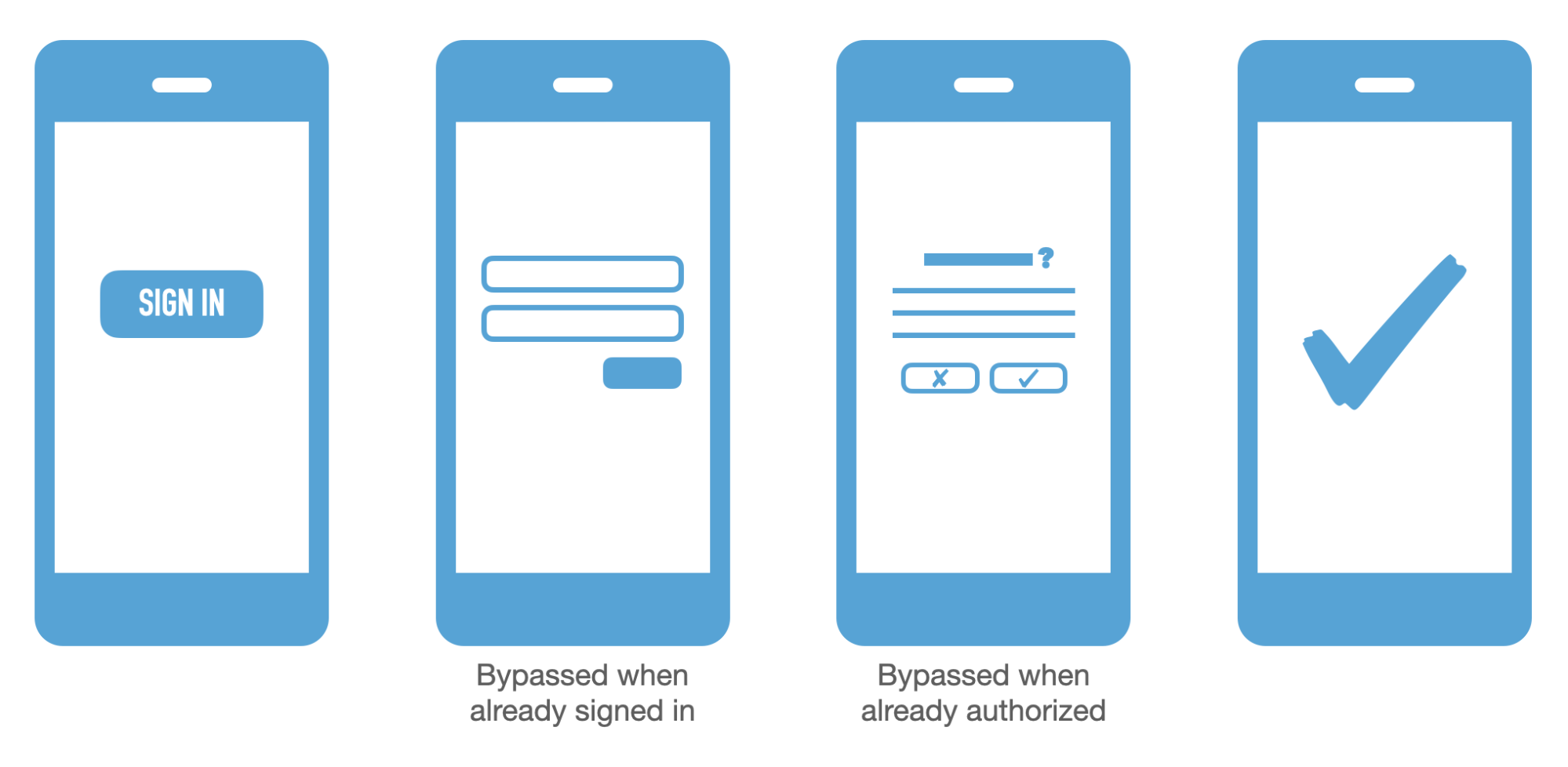

A typical sequence when logging in to an application is to click the “log in” button, enter your credentials, be prompted with a consent screen, and be redirected back to the application.

The authorization server may choose to skip the credential prompt if the user is already logged in. The authorization server may also choose to skip the consent screen if the user has already consented to this application before or for first-party apps. In that case, the redirect would be immediate, which is good for user experience, but bad if client impersonation is possible. Again, this isn’t a concern for confidential clients since client impersonation isn’t a concern if the client can authenticate. But for public clients, since the OAuth flow is done with only public information, client impersonation is definitely possible. That said, the original OAuth 2.0 specification actually calls this out explicitly in the Security Considerations Section 10.2. The recommended mitigation from the original spec is to require redirect URL registration and to avoid skipping the consent screen. This gives the end user a chance to spot any attempts at tricking them into authorizing a malicious application.

Gaining privileged API access

Some services may restrict certain APIs for use only by specific clients. If the service has some APIs that should only be called from a particular mobile app, the service may want to reject requests made from other apps that are accessing other parts of the system. Additionally, some services may set different API rate limits for different clients depending on the trust level of the developer or whether the client is a first-party or third-party client.

In order to do this, the API needs to know which client an access token was issued to. Typically, the authorization server will embed the application’s client_id in one of the claims of the access token. In this way, the client_id is accessible to the API when it validates the token. Of course, this information is only as good as the authorization server’s confidence that it was really that app making the token request. Again, if the client can authenticate itself, then this is reasonably reliable. But for public clients, there is much less certainty.

Keep privileged access in mind when you’re building APIs that limit features based on the application.

Frequently asked questions

With these concerns in mind, let’s answer a few quick questions about OAuth client impersonation.

Is client impersonation a new problem?

Not at all! In fact, client impersonation was mentioned in the original OAuth 2.0 spec RFC 6749 in 2012! The next year, the “Threat Model and Security Considerations” document was finished and became RFC 6819. This document has a large section dedicated to the topic of client impersonation. That section is worth a read for more information on various ways to mitigate this risk.

Is client impersonation a problem unique to OAuth?

Client impersonation is relevant to OAuth for the reasons previously mentioned, but those issues may also be relevant to systems that don’t use OAuth at all.

This is a pervasive problem with mobile app games. Let’s take a simple example of building a leaderboard service for a mobile game application. For the sake of the example, let’s assume the app doesn’t have any concept of user accounts, and wants to show a high score leaderboard in the game from all users of the app worldwide. In order for the game server to collect the high score data, it provides an API endpoint that the game can report scores to. The API would like to only accept POST requests from real instances of the game app, and not people who are trying to cheat and send fake scores to the API.

Without the support of the mobile operating system, there’s nothing in the API call that can authenticate the mobile app, since any HTTP request the app makes would be possible for anyone to mimic outside of the application.

Does PKCE solve client impersonation?

Nope! This is a common point of confusion, likely because of how PKCE was originally developed and rolled out. PKCE was originally described as a way for a mobile app to do the authorization code flow safely. But keep in mind this was back in 2015 when mobile apps were still advised to use the Implicit flow or the authorization code flow without credentials.

Despite PKCE being originally described as a technique for mobile apps, it is not an alternative to client authentication and doesn’t ever attempt to pretend it is. PKCE prevents a few specific attacks, mainly authorization code interception and authorization code injection. And interestingly, authorization code injection is also possible even if the app does use a client secret or other client authentication. That’s the reason PKCE is now recommended for all types of OAuth clients, regardless of whether they are a mobile app, a SPA, or a server-side app with credentials.

At the end of the day, PKCE is not a form of client authentication, so it doesn’t solve the client impersonation problem. PKCE is still a good idea to use since it prevents other notable attacks.

Are there any solutions for client impersonation?

As of today, there aren’t any reliable mechanisms for authenticating pure SPA clients in a browser. Anything the browser can do can be mimicked outside the browser. Google Chrome even has a developer tool that lets you copy any request the browser makes as a cURL command to be replayed on the command line.

For mobile apps, there is more hope. Apple has an API known as “App Attestation”, and Google has a similar API called “Google Play Integrity”. Both APIs work similarly, with a few technical differences. At a high level, both of them involve the application making a request to the operating system to sign some data. Then the app includes that signed string in the call it makes to the developer’s API. The API can validate the signature against the public key from Apple and Google to determine its confidence level that the API request is made from a real version of the mobile app.

The intent of these mobile operating system APIs is to give the developer a way for a web service to validate that a request is being made on a non-jailbroken device with a legitimate app store instance of an application. Interestingly, in both cases, Apple and Google have specific language in the documentation that suggests these should be used as hints, but not guarantees, of app integrity.

Does the BFF pattern solve client impersonation?

The BFF pattern, short for “backend for frontend”, is the idea of running a backend service to supplement a single-page application. There are multiple variations of how this can be deployed, some of which are documented in the OAuth for Browser-Based Apps draft specification.

The key difference this makes with regard to OAuth client impersonation is that your backend can be the OAuth client and can use client authentication. If the backend holds the tokens without sending them to the SPA at all, then the tokens can never leak to an impersonating application. While this might sound good at first, your backend has no assurances that any requests made to it are from the legitimate SPA, so the problem is only half solved. This does makes the problem less severe, since someone trying to take advantage of client impersonation wouldn’t be able to actually get the access token itself, but would only be able to trick the backend into making API requests with that access token.

Future solutions for client impersonation

I mentioned this had been a recurring theme in the recent discussions within the OAuth community at the last several events. I presented a session about client impersonation specifically in mobile apps at the OAuth Security Workshop. The session wasn’t recorded, but I posted the slides here. In that session, I suggested the idea of leveraging Apple and Google’s app attestation APIs as a form of client authentication. In a side discussion after the talk, we heard from a group who had actually implemented that for a client recently, which was a nice validation of the concept. Separately, George Fletcher presented a session at EIC 2022 the following week about nearly the same topic! I’m glad to see this recognized as a need for mobile apps.

As far as browsers go, I think we’re farther off in finding a similar solution, since browsers don’t have the same level of tie-in with the operating system that mobile apps do. With the advent of modern browser APIs like WebCrypto and WebAuthn, it’s possible we may see something similar in the future.

Is client impersonation something you should be concerned about? It really depends on your situation, in particular whether you have any policies in place that treat particular public clients differently from others.

If you’d like to learn more about OAuth, check out my OAuth videos on our YouTube channel, or tune in to an upcoming OAuth Happy Hour livestream!

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.