The Dangers of Self-Signed Certificates

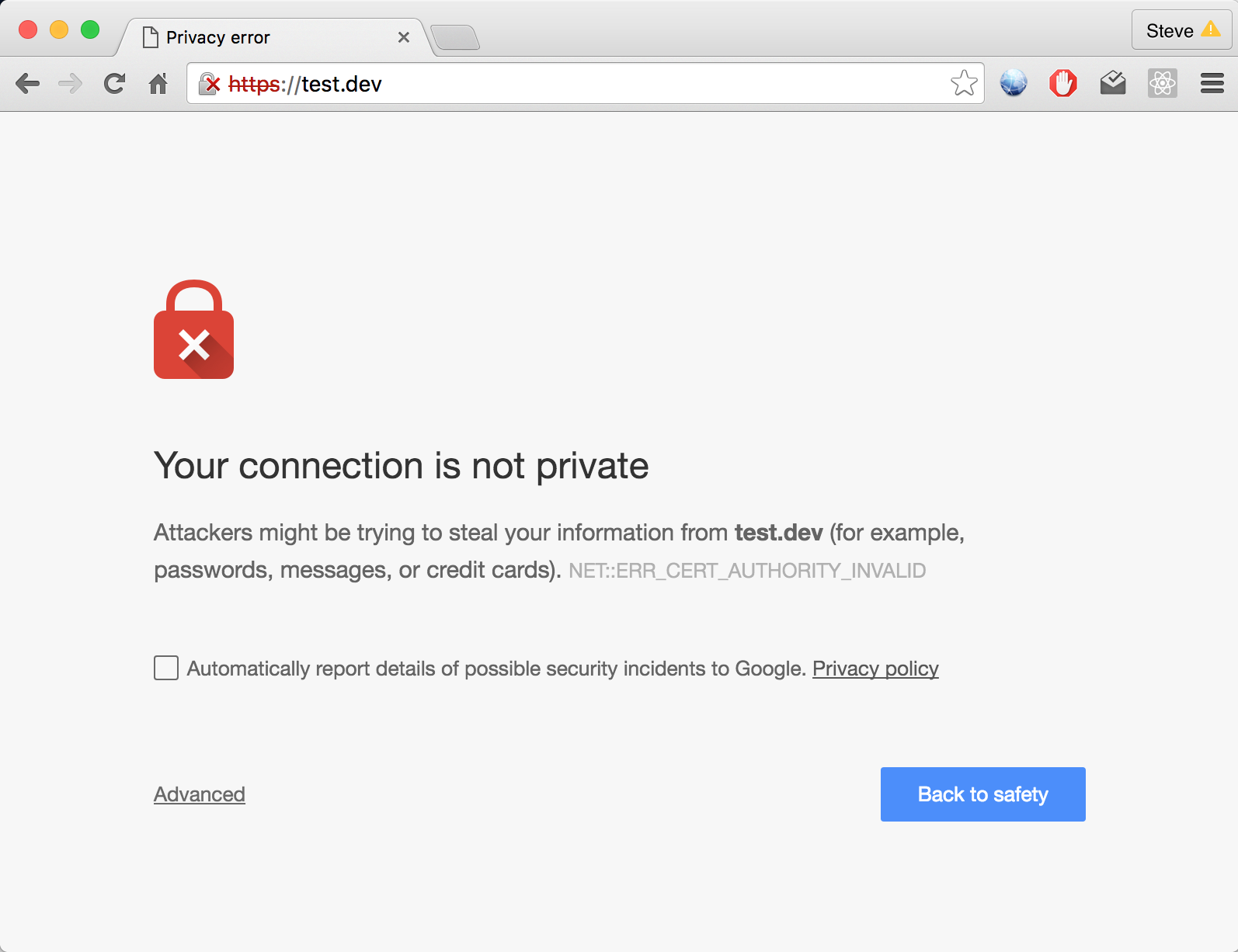

How many times have you started a new job, and the first thing you see on the company intranet is a “Your connection is not private” error message? Maybe you asked around and were directed to a wiki page. Of course, you probably had to click through the security warnings before actually viewing that page. If you are security-minded, this probably bothers you, but because you have a new job to do, you accept the warning and proceed to jump through the hoops of installing the certificate.

The most dangerous phrase in the language is, “We’ve always done it this way.” -Rear Admiral Grace Hopper

The Chain of Trust with Digital Certificates

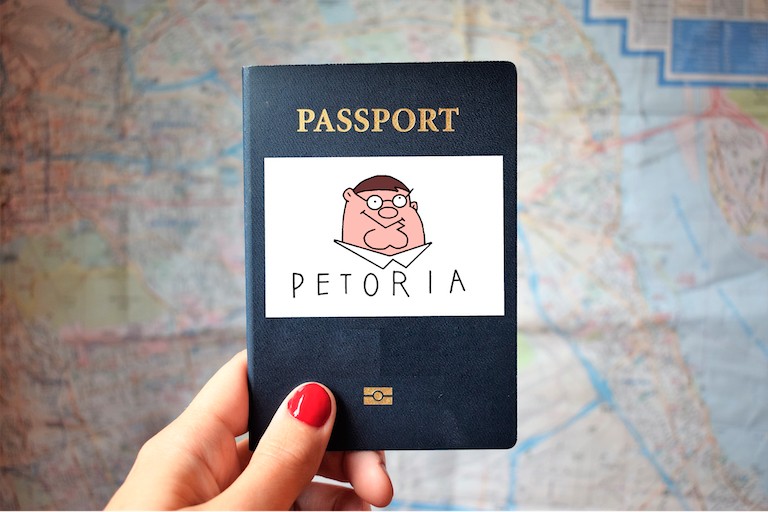

Before we continue, let’s talk about how a typical certificate works by using a passport analogy. A passport (the certificate) is issued by a government body (the authority). A customs agent who trusts the authority can validate the passport.

I can create my own passport, but no customs agent will validate it - it has no originating authority. The same holds true for certificates.

A typical TLS certificate has more than one authority involved. A “root certificate authority” that issues an intermediate “certificate authority” (CA), that may issue another intermediate CA, which finally issues the certificate for a site.

Extending the passport analogy a little, we could liken this to European Union (EU) passports. The EU grants authority to Sweden, which issues passports to individuals. If you trust the root EU authority, you are implicitly trusting Sweden’s authority and all of the passports they issue.

Verifying a digital certificate is more complicated than getting a stamp on your passport, and outside the scope of this post, this short post covers the math involved.

Inspect the Chain of Trust

We can look at a site’s certificate using OpenSSL:

openssl s_client -connect developer.okta.com:443 -servername developer.okta.com

Near the top of the output will be the “Certificate chain” section:

Certificate chain

0 s:/C=US/ST=California/L=San Francisco/O=Okta, Inc./OU=Technical Operations/CN=developer.okta.com

i:/C=US/O=DigiCert Inc/OU=www.digicert.com/CN=DigiCert SHA2 High Assurance Server CA

1 s:/C=US/O=DigiCert Inc/OU=www.digicert.com/CN=DigiCert SHA2 High Assurance Server CA

i:/C=US/O=DigiCert Inc/OU=www.digicert.com/CN=DigiCert High Assurance EV Root CA

This shows that a DigiCert (a root CA) issued a CA to DigiCert High Assurance Server, which then issued a certificate for developer.okta.com.

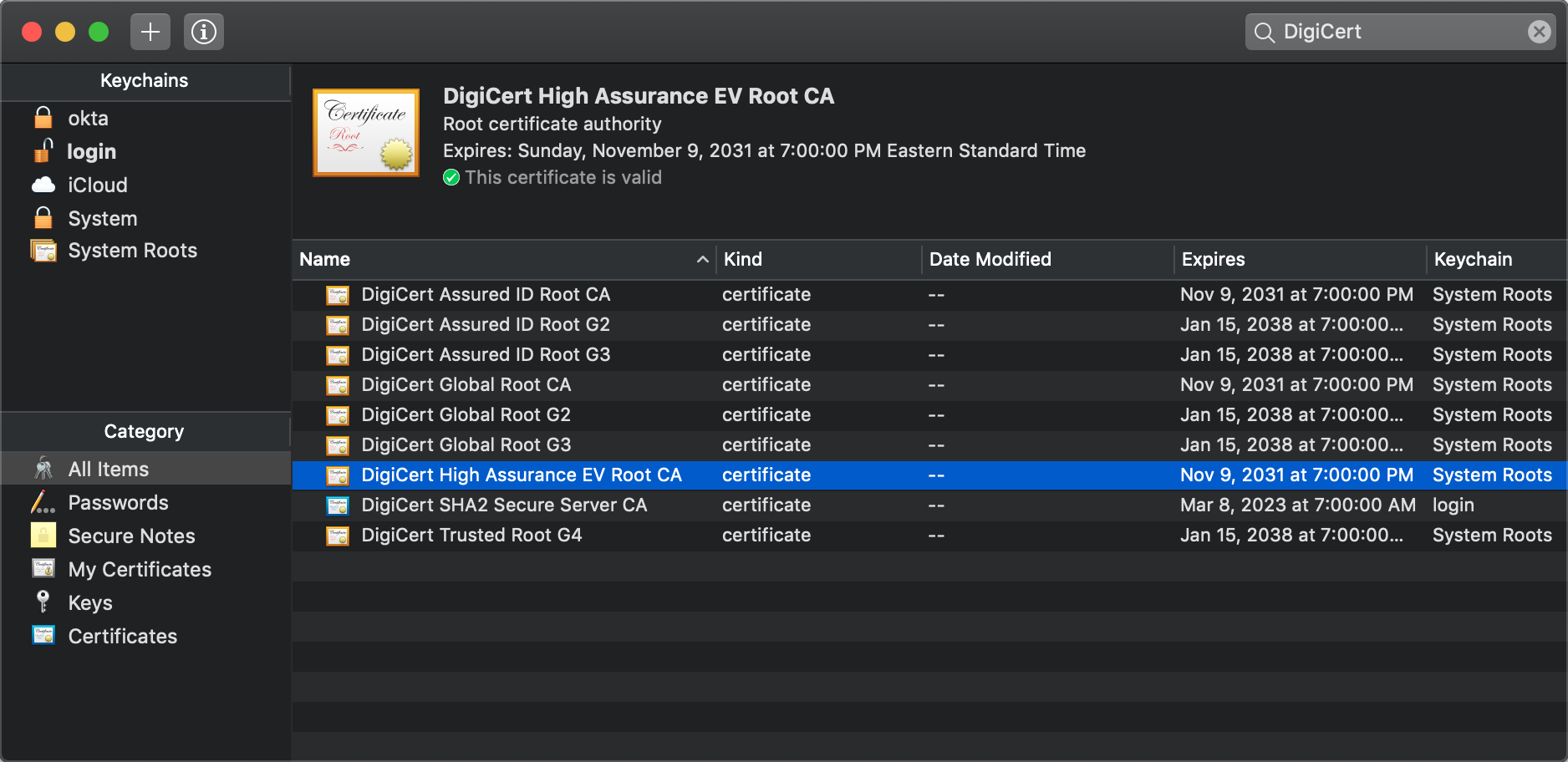

On my MacBook, using the “Keychain Access” application, I can see that the DigiCert CA is trusted. Therefore any certificates signed by that CA are trusted.

No Chain of Trust for Self-Signed Certificates

A root CA is a trust anchor, where trust is assumed and not cryptographically derived. Because of this, officially trusted root CAs are governed by a standards body (Certificate Authority Security Council) and bound by a rigid set of standards. The key rotation ceremony alone can take up to eight hours! These standards and transparency allow us to trust them.

Your self-signed key has none of this; if you are lucky, you have an outdated wiki page describing the process.

Often, a company’s self-signed keys are not managed securely. If an attacker (or disgruntled employee) can get access, they could create a site like evil.my-corp-intranet.com, and all of your employees could be susceptible to an attack.

Access to self-signed CAs needs to be heavily restricted. Publicly trusted root CAs use hardware security modules (HSM) with tamper protection to prevent and audit access.

Self-Signed Certificates Train Internet Users to be Less Secure

My biggest complaint about self-signed certificates or CAs is that their use introduces a dangerous behavior. It doesn’t take too many times for a person ignoring a security warning to form a habit. Think about the last time you actually read a click-through license when installing software, nobody reads them. Do you really want to train your employees to do the same thing for security?

Self-Signed Certificates Kill Developer Productivity

Managing self-signed certificates across your developer tools is a royal pain. More often than not, these tools do NOT use the OS key chain. This means developers need to configure each one independently. For example, with Java, you would use keytool, and is typically set up once per JVM installation (and any time you install a new JVM). With NPM, developers need to configure the cafile setting. When you do this, ALL your NPM repositories will use this CA, which likely means any public GitHub project will fail to build.

These are just two common examples, but there are similar “workarounds” for Python, PHP, etc.

Free Certificate Alternatives

Last time I checked, becoming a certificate authority for a single domain costs up to six figures, which is probably why self-signed keys are so pervasive today. This isn’t an option everyone can afford. Luckily we have Let’s Encrypt, which will issue you free certificates. These certificates only last 90 days, but can also be configured to auto-renew, taking the human error element out of the picture. Even better, many online hosting services will automatically manage certificates for you: Netlify, Heroku, and Firebase.

When is it OK to Use a Self-Signed Certificate?

Self-signed certificates are not always a bad idea. I use them for development and automated testing of services that require TLS. In these cases, the chain of trust starts and ends me. The tool mkcert makes setting up your development environment trivial by generating a certificate and adding it to your local trust stores automatically with a single command.

Feel free to leave comments below. To make sure you stay up to date with our latest developer guides and tips, follow us on Twitter and subscribe to our YouTube Channel! We’ve also got a new security site you should check out if you’re interested in other security-focused articles.

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.