Whiteboarding for Developers: Yes, You Have To

I’ve always thought developers are a pretty rare collection of individuals. We all vary in our composition; from the quiet introverts to the boisterous extroverts, from button-downed professionals to aloof loose cannons – we run the full spectrum of human personalities. However, we are unique in that we share a set of common traits that are really only understood by us.

Our parents might not really know what we do:

“He works with computers”

Our non-developer friends do know, but they can’t fathom why we do it:

“Seriously, if I had to stare at a computer screen all day, looking for a missing semicolon, I’d jump out a window!”

Yet, we love doing it. Love turning blank screens into works of digital art. The problem is, we like this so much, that we don’t like being pulled away to do things ancillary to the work itself. Case in point – whiteboarding.

Why Whiteboarding is a Must

I want to be a coder forever, so leave the whiteboarding to architects, analysts, and managers. You know, people who like meetings.

Nobody likes meetings. However, they do serve a purpose and it is important, even if you don’t want to ever change your career path, to know how to navigate them. Meetings aren’t the only place where whiteboards happen either. Whiteboarding happens anytime you need to visually represent an idea or process to reach a solution. Note that I didn’t add “…with other people” to the end of that sentence. One of the most useful aspects of whiteboarding is the ability to do it for your own benefit.

Remember when I said developers share some common traits? Well, one of those traits is a super-charged and somewhat organized imagination. We can use our brains to translate the needs of the customer into the needs of a system and then overlay the mechanics of how to achieve that in syntax. That’s not exactly eyes shooting laser beams, but it’s not too shabby. The problem we tend to have is that when we try to actually explain what’s in our head to others; we have trouble. That’s why our parents still don’t understand what we do and our friends can’t see the art of it. It’s hard to verbally relate what’s going on up there between our ears.

Whether you are trying to articulate a concept to yourself or others, whether you are explaining something that already exists or attempting to divine a solution for a problem – knowing how to translate what’s happening in your brain to a visual that others can consume is important.

Whiteboarding is Not About Art, It’s a Skill

I can’t draw worth *$$!@$

Me neither. Funny thing is, I can see the picture in my head, usually. I can see it, I can envision drawing it. Even something so simple as a square or cylinder and then I try to draw it and it looks like a Rorschach test.

You need to look at whiteboarding like any other thing you’ve had to learn to do before. Oh, and it’s not about physical prowess either. Because it is mechanical and tangible, I think some people feel like drawing equates less to art and more to a sport. No matter how much I practice, my brain won’t let me consistently swing a golf club correctly three times in a row. Whiteboarding output certainly can lose quality when you are distracted, nervous, or complacent – but that’s true of anything. Whiteboarding is more like cooking, I think. There’s a skill to organizing what must be done and then mapping the simple series of physical steps to the time allotted and getting it all to come out right in the end. If you can make Mac & Cheese, you can do this. Yes, making Mac & Cheese is a skill (I hope you didn’t think it was an art).

Tips for Developing Your Whiteboarding Skills

I’ve hopefully made my case for why and bolstered your spirits enough to make you think you should try. Now, let’s break this down a bit into some usable tips.

Practice

Like I said earlier, you don’t need to present to anyone other than yourself. I use a whiteboard a lot. When I’m stuck with a problem or just can’t seem to get my use case to make sense – I’ll find a board or a notepad and try to scribble out what I’m wrestling with. If I can’t manage to get the parts and components to arrange on the page, it usually means I don’t have a full grasp of what I’m trying to do.

You should practice the tips I’m going to list below. You should practice it every time like it’s something you are doing for others. If you don’t have access to a whiteboard outside a meeting room – just use a piece of paper. I wouldn’t suggest using software diagramming tools. They are fantastic, however, to borrow from my cooking analogy above, that’s a little like cooking a take-and-bake pizza. We need to work on our cooking skills now. One last thought on practice: Go back a day or even a week later and look at your work. Do you get it? Are you confused or unable to read what you did? Don’t beat yourself up! Realize there is still a disconnect between what you see in your head and what you can physically represent. It is a skill, so keep practicing it. Ever sing along with the radio and think “wow, I can really hit that high note” and then try it with the radio off and realize you suck? Yeah, all the time for me. Same thing here, when you are drawing for yourself you can’t see the skipped pieces of logic or missing words because they are already in your head. You can hear the music while drawing, so you need to go back and look later when the music isn’t playing.

Pause First

One of my favorite 80’s songs is Poison’s “Every Rose Has Its Thorn”. Yes, it’s cheesy, shallow, and a little silly – but let’s not judge ok? The first 5 seconds of that song is a simple, calming deep breath. Check it out, it’s not that creepy.

We have a tendency to leap from our chair to go draw on the board or maybe the opposite: be paralyzed with fear and stumble up there consumed with confusion. Just. Stop. Take 5 seconds and breathe. Use this time to survey the whitespace and imagine what you need to put there. Think about how you will structure your thoughts or what thoughts you need to structure. If you need to, try to not think about anything for that 5 seconds. When you walk to the board just take a moment and prepare. If somebody tries to jump in and speak, that’s their problem. Let them be rude, you do your thing.

Develop Your Strategy

This is where practice pays off. When you wrote an essay for school, you knew you couldn’t just free form you’re way through it. You needed structure. You needed purpose. You needed a point. Again, that’s a skill.

How you use a whiteboard requires a strategy. You certainly can and should develop your own style, but here’s one that works for me.

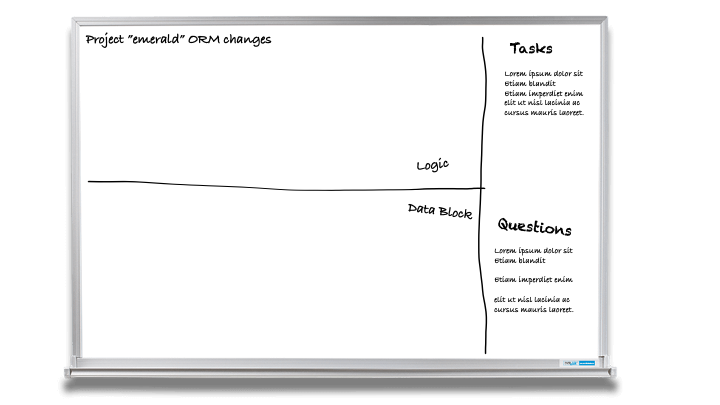

Reserve a portion of the board for lists and draw a dividing line to identify it first. This could be tasks that you uncover, requirements you need to show, questions that arise… whatever. When you finish your session, this area is now a clear, segmented, and concise area to capture to-do items or check-off deliverables. If you don’t reserve this space at first, you’ll have these items spread all over your picture and it won’t look like annotations – it will look like crap.

In the remaining area, decide if you need to break it down further. Do you have multiple categories or components? For instance, do you need to reserve a section for application tiers? What about two different systems? If you can determine these high-level categories, draw dividing lines to reserve space for things representing parts of those sections. Again, draw these right away.

At some point, put a title on the drawing and be sure to label the categories and lists sections too. If you’ve done your job right, somebody will take a photo of this whiteboard and it will become documentation or the seed of documentation. Treat it that way so it can be consumed and understood without you as a tour guide.

You should also know when you are done. If the conversation diverts from your understood purpose, as happens a lot with brainstorming sessions, it’s ok to stop. If there’s another board, move there and start over. If there isn’t another board, don’t try to turn the apple you’ve drawn into an orange. Take a picture first if that’s wise, but otherwise, send your drawing where it’s destined to go anyway – to the final justice of the eraser.

Shape It

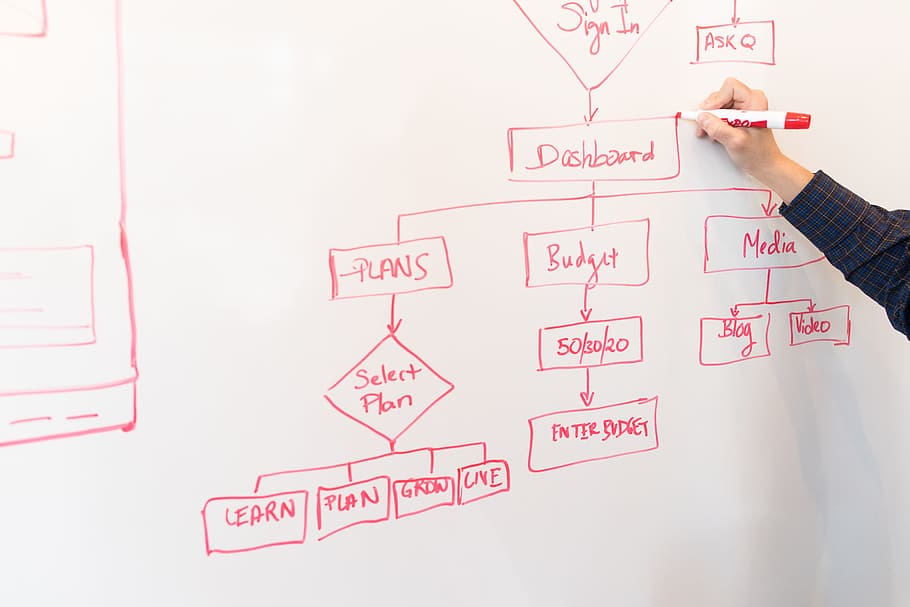

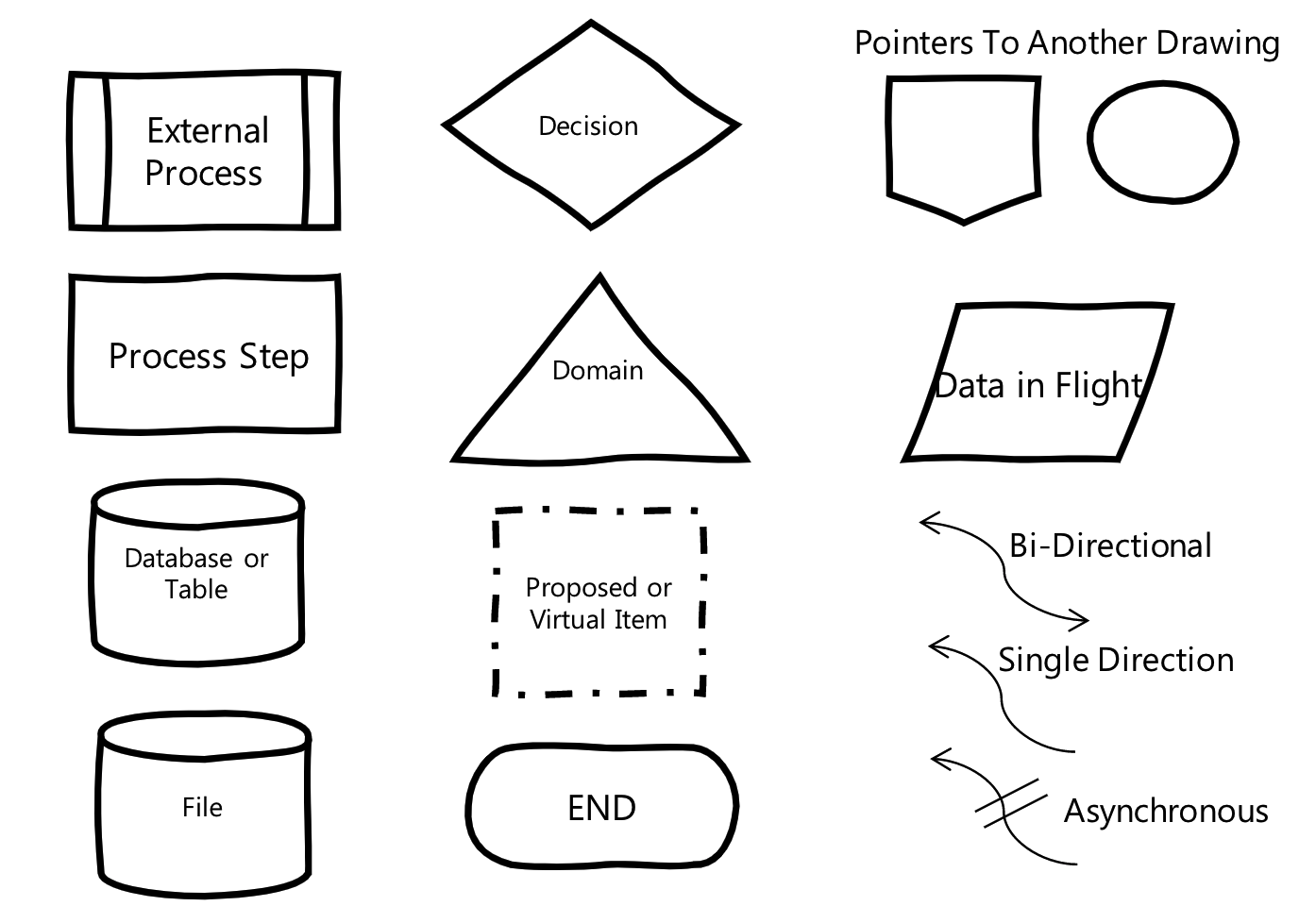

Decide in your strategy what shapes mean. If you haven’t studied basic flowcharting, you should. Like it or hate it, flowchart shapes aren’t some extinct or specific communication technique like naval signal flags. A rectangle means something different than a triangle and for good reason: I may not know what you are trying to show me at a glance in your diagram, but if I understand this basic flowcharting standard and you are respecting it, then you’ve just built a boat that floats and I’m on board to see where we are sailing off to.

Now don’t take this to the extreme, of course. Take some liberties with how you use your shapes like I’ve done in the image examples here. Once you decide on what a shape means and you’ve told your audience of its significance (e.g. this box with a double vertical line is a pre-existing application we are connecting to), stick to that. Again, if your drawing becomes a digital graphic and therefore documentation, make it so it can stand on its own without bespoke description.

In your practice, practice drawing your shapes properly. Make them crisp, clear, and repeatable. It is not art, it is a skill. Practice. Practice. Practice.

Color is Cute

Consider color when you are pausing and taking a breath. Look at the tray and decide what colors are there and how you might use them in an interesting or specific way. However, do not rely upon color to tell your story. If you think color is important rather than just cute, let me tell you why I think you are wrong:

You Can’t Be Sure That You’ll Have Enough Colors

Even if you bring your own with you in a custom leather bag with your initials on it, what’s the right number of markers? What Crayola or Pantone scale of color is the right number to map to any number of categories you might have? Before you quote Fibonacci or your Master’s thesis on the topic let me stop you. It doesn’t matter. Color is not a description and it is not a shape. You can use it to identify something ancillary (like coloring new units of work a different color from unchanged parts of a system). However, that is information that if lost does not detract from the impact of the drawing.

Color Cannot Be Trusted as a Definition of a Type

This one is simple. I’ve already said you can’t rely on having a firm definition of the quantities of colors needed to define everything. In this context though, let me tell you it doesn’t matter.

People can be color blind. They may not be able to tell one color from another. Being color blind is also not a singular thing. Tritanopia, Deuteranopia, Protanopia, and several other types of color blind definitions exist each of which resulting in a different view of what we understand as a color. So, you can’t even create a matrix of “well, if you see color like I do this is red, if not it’s blue”. That varies by the person.

Perhaps the best reason not to use color is the consideration of your audience. Forget your need to be understood. Do you really need to risk embarrassing somebody just to use fuchsia to distinguish POST from PUT?

Color is a Distraction

The composition of your drawing gets busier with more color because it is more to process and detracts from your audience’s ability to study what you are trying to convey.

Don’t forget that the constant changing of markers and capping/uncapping is also a distraction.

Color is Not Forever

Always remember this drawing may live forever in a document or note to act as documentation. It could get printed out or even photographed in grayscale.

Back in Black

I just spent a lot of your and my time talking about why not to rely on color as anything other than an ancillary tool. I’m going to make one exception. Buy your own black marker and carry it with you. Black will get used the most in a conference room and tends to dry out. Rather than be forced to draw your complex diagram in unreadable orange or piercing neon green, have your own marker at the ready.

Fill Your Space

You’ve got your shapes practiced and have a solid strategy to arrange your drawing in the space provided. Now, use that space. Make your shapes and words large enough to be able to be seen and read.

How many times have you seen someone write their text in the equivalent of 6 point font; leaving an alabaster sea of whiteboard and a squiggle of black text in a corner? Arrange your shapes like you would furniture in your living room. Think about the traffic patterns and where you’ll draw connectors or lines. What’s most important and needs to be emphasized? What types are actually super-types that need to be larger boxes to hold smaller boxes inside them?

You’ll be surprised that after practicing and doing this work a few times how much better you’ll get at sizing to the space and adjusting as you go to the space remaining.

It Will Be Okay

I waited until the very end of this post to address the elephant that stands between your chair and the whiteboard. It’s scary to stand up in front of your peers or superiors. It’s scary to stand up in front of those who are junior to you and are expecting great things. Make no mistake, I wouldn’t even begin to minimize any of that. I intentionally set all the mechanics of whiteboarding up first so I could deal with the real barricade here: our own fear.

Do you remember the first time you had a code review? Terrifying. “They will hate all my code. They’ll learn I’m not supposed to be here. They’ll expose that I didn’t listen close enough or understand the business problem.”. It was hard to get beyond that and, hopefully, as a human being, you took that experience with you forward to the code reviews you now perform. You show benevolence and temperance and provide constructive criticism so everyone gets better. If you don’t think that’s your responsibility as a person, you should at least acknowledge it’s your job.

It’s like that with whiteboarding. It’s scary. It’s also scary for the person you’re watching do it. You can learn from what you see and they can learn from how you react. The point of whiteboarding is to efficiently convey ideas and/or reach a solution. It takes a presenter and a consumer for it to be a successful endeavor. As I’ve said all along, this is about skill and not art. Therefore, your abilities and comfort level can be improved with practice, iterations, and an equitable team.

Finally, I hope these thoughts and tips will both show that whiteboarding is necessary and that it’s nothing to fear. Done well, you can have an effective tool to improve your project, solution, or even career. Developers are unique people with unique skills. Adding this collection of skills might allow you to bridge the gap from what you understand to something everybody can understand.

Learn More About Developer Career Topics

If you liked this post, you might like some of our other developer-related topics:

- Why Every Developer Needs to be a Generalist

- Pro Tips for Developer Relations

- Container Security: A Developer Guide

Want to be notified when we publish more of these? Follow us on Twitter, subscribe to our YouTube channel, or follow us on LinkedIn. If you have a question, please leave a comment below!

Okta Developer Blog Comment Policy

We welcome relevant and respectful comments. Off-topic comments may be removed.