On this page

Federated Identity

Federated identity is a way to use an account from one website to create an account and log in to a different site.

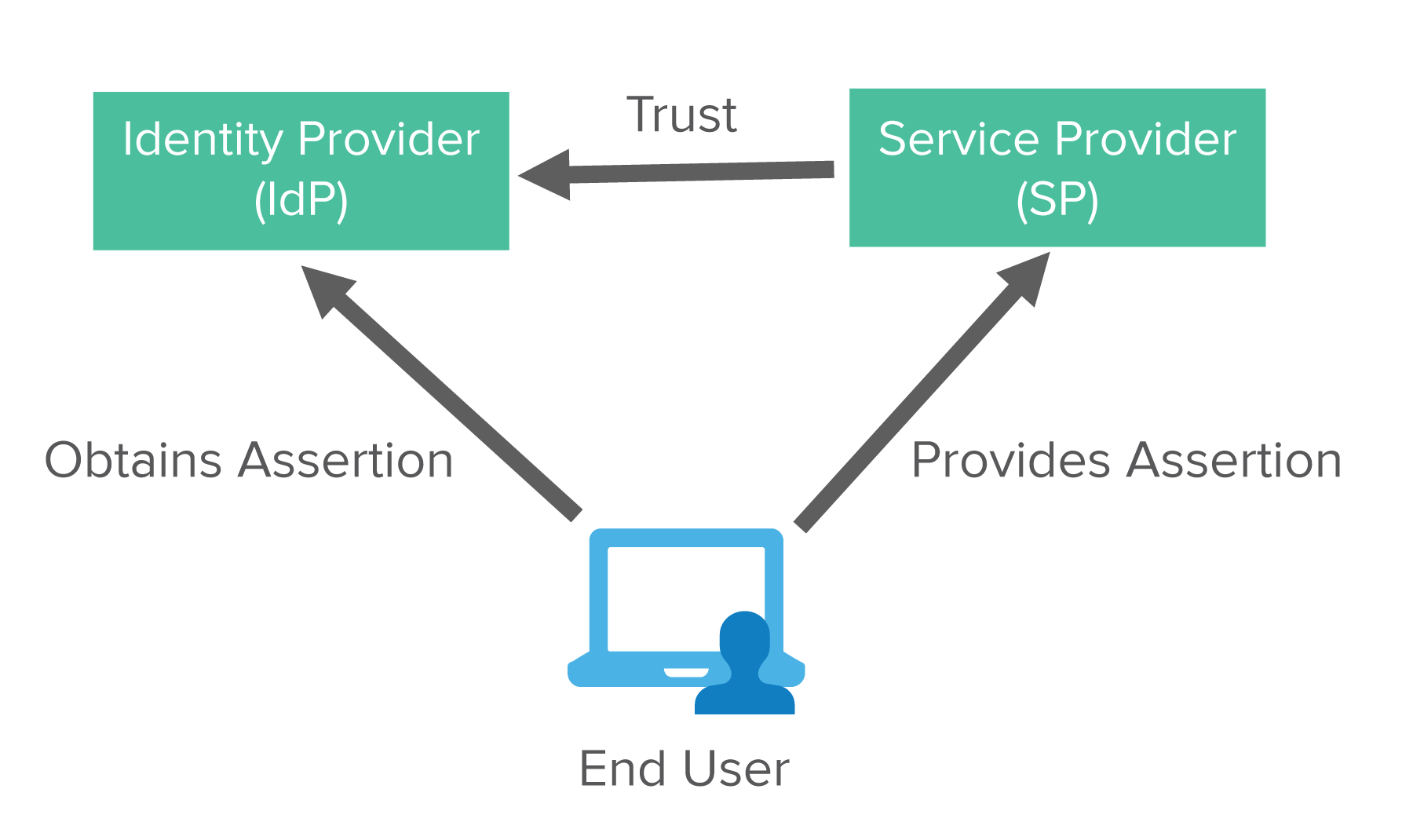

There are two main players in a federated identity system: an Identity Provider (IdP) and a Service Provider (SP). Often, the service provider is the application that you need to log in to, and the IdP is the provider of the users that can log in.

OAuth 2.0

OAuth 2.0 is a delegated authorization framework which is ideal for APIs. It enables apps to obtain limited access (scopes) to a user's data without giving away a user's password. It decouples authentication from authorization and supports multiple use cases addressing different device capabilities. It supports server-to-server apps, browser-based apps, mobile/native apps, and consoles/TVs.

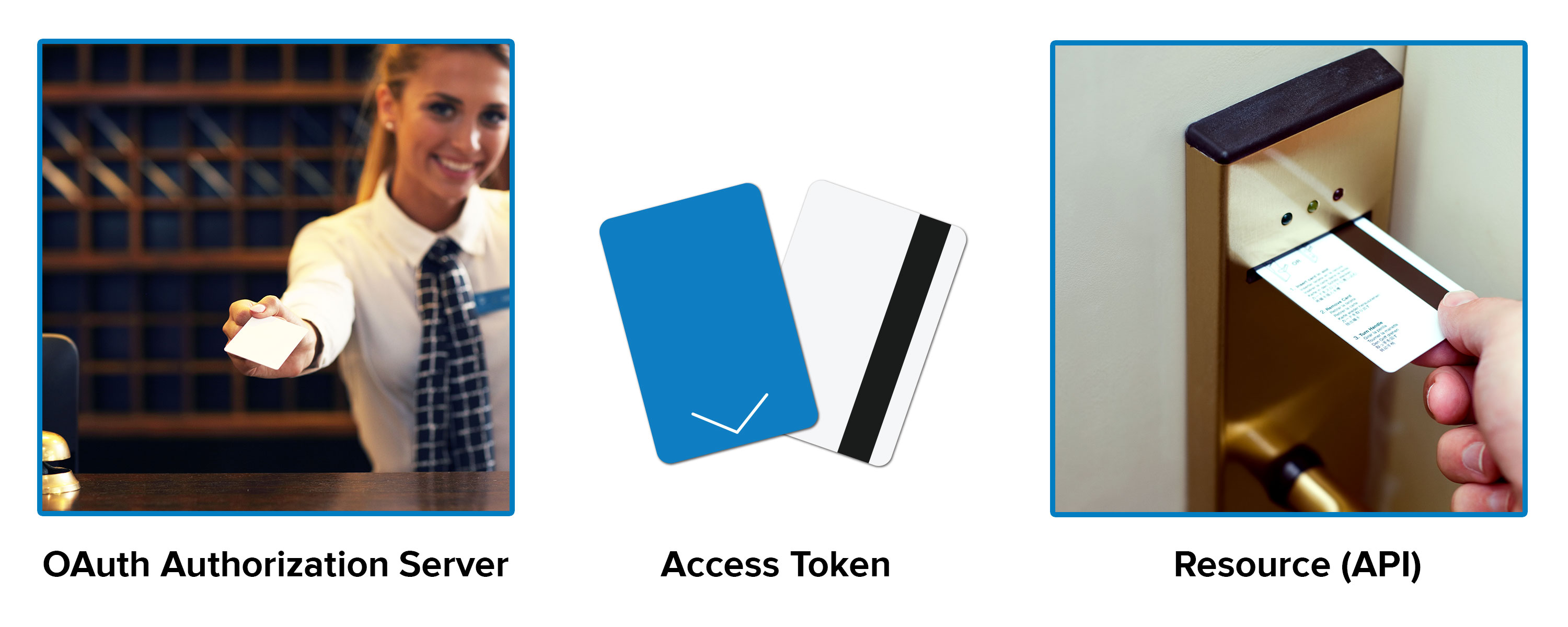

OAuth is like a hotel key card, but for apps. If you have a hotel key card, you can get access to your room, the business center, and potentially the gym. How do you get a hotel key card? You have to do an authentication process at the front desk to get it. After authenticating and obtaining the keycard, you can only access the places and things the hotel has authorized you to use.

To break it down simply, OAuth is where:

- App requests authorization from User

- User authorizes App and delivers proof of authorization

- App presents proof of authorization to the authorization server to get a Token

- The Token is restricted to only access what the User authorized for the specific App

- Resources (APIs) validate the Token as having the proper and expected authorizations

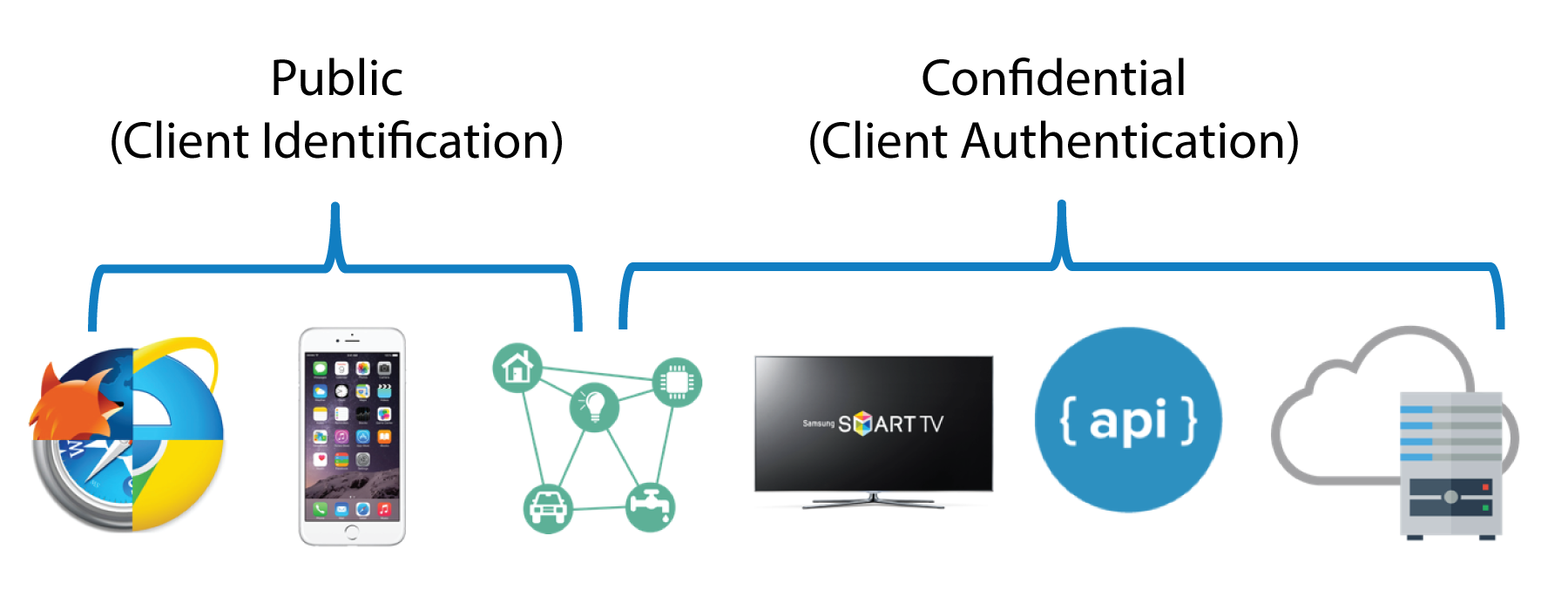

Client applications can be public or confidential. There is a significant distinction between the two in OAuth nomenclature. Confidential clients can be trusted to store a secret because they have backend storage unavailable to review or attack. They're not running on a desktop or distributed through an app store. People can't reverse engineer them and get the secret key. They're running in a protected area where end users can't access them.

Public clients are browsers, mobile apps, and IoT devices. The code on these devices can be extracted, decompiled, and reviewed. Therefore, we can't store any sensitive information in the application itself and expect it to be protected. Do not embed a password or secret information - including URLs - of any form in these types of applications!

The core OAuth specification describes two types of tokens: an access token and a refresh token. The client uses the access token to access an API (aka Resource Server). They're meant to be short-lived and work over a span of minutes or hours, not days or months. Due to this, the core OAuth specification doesn't have an approach to revoking access tokens but in many cases you will need to as a token could have been compromised or a subscription has expired. To address that RFC 7009 (opens new window) describes an additional endpoint to revoke a token. To be specific, this revokes it with the Authorization Server, not the Resource Server (API). Unless the Resource Server checks with the Authorization Server, it will not know the token has been revoked. This happens in the real world where you could still use your driver license to board a flight, even if it has been revoked.

The other token is the refresh token. This is much longer-lived and may last for days, months, or years. This token is used exclusively to get a new access token. Because a refresh token effectively persists access long term, getting them requires a confidential clients and they can be revoked more easily.

Next, the OAuth spec doesn't define how a token is structured, its contents, or how it's encoded. It can be anything you want but generally you'll want a JSON Web Token (JWT) as defined by RFC 7519 (opens new window) In a nutshell, a JWT (pronounced "jot") is a secure and trustworthy standard for token authentication. JWTs allow you to digitally sign information (referred to as claims) with a signature and can be verified at a later time with a public/private key pair.

Tokens are retrieved from endpoints on an authorization server. The two main endpoints are the authorization endpoint and the token endpoint. They're separated for different use cases.

The authorization endpoint is where the app goes to get authorization and consent from the user. This returns an authorization code that says the user has consented to the app's request. Then the authorization code is passed to the token endpoint which processes the request and says "great, here's your access token and your refresh token."

Now you use the access token to make requests to the API. Once it expires, you use the refresh token with the token endpoint to get a new access and refresh tokens.

Because these tokens can be short-lived and scale out, they can't be revoked; you have to wait for them to time out.

OAuth uses two channels: a front channel and a back channel. The front channel is what goes over the browser. The back channel is a secure HTTP call directly from the client application to the resource server, such as the request to exchange the authorization code for tokens. These channels are used for different flows depending on what device capabilities you have.

To address the differences between web apps, mobile clients, IoT devices, and even other APIs, there are numerous OAuth grant types or flows. The first four are defined in the core specification while the other three come from extensions.

Implicit flow - everything happens in the browser, on the front channel. Common in single page applications (SPAs).

Authorization Code flow - the front channel is used to get an authorization code. The back channel is used by the client application to exchange the authorization code for an access token (and optionally a refresh token). This is the gold standard of OAuth flows.

Client Credentials flow - often used for server-to-server and service account scenarios. It's a back channel only flow to obtain an access token using the client's credentials. It differs from most of the other flows in that there is no user involved.

Resource Owner Password flow - a legacy flow that allows you to pass a username and password to the authorization server. Only recommended when you have old-school clients to accommodate.

Assertion flow - similar to the Client Credentials flow. This was added to open up the idea of federation. This flow allows an Authorization Server to trust authorization grants from third parties such as SAML IdP. The Authorization Server trusts the Identity Provider. This is described further in RFC 7521 (opens new window).

Device flow - often used with TVs, command line interfaces, and other devices without a web browser or with limited input options. The device first obtains a short "user code" from the authorization server, and the device prompts the user to enter that code on a separate device such as their mobile phone or computer. The client polls the authorization server via a back channel an access token, and optionally a refresh token is returned after the user authorizes the request. This is described further in the OAuth Device flow draft spec (opens new window).

Authorization Code flow + PKCE - the recommended flow for native apps on mobile devices. In this flow, the native app sends a PKCE code challenge along with the authentication request. This is described further in what's commonly known as the "AppAuth spec (opens new window)".

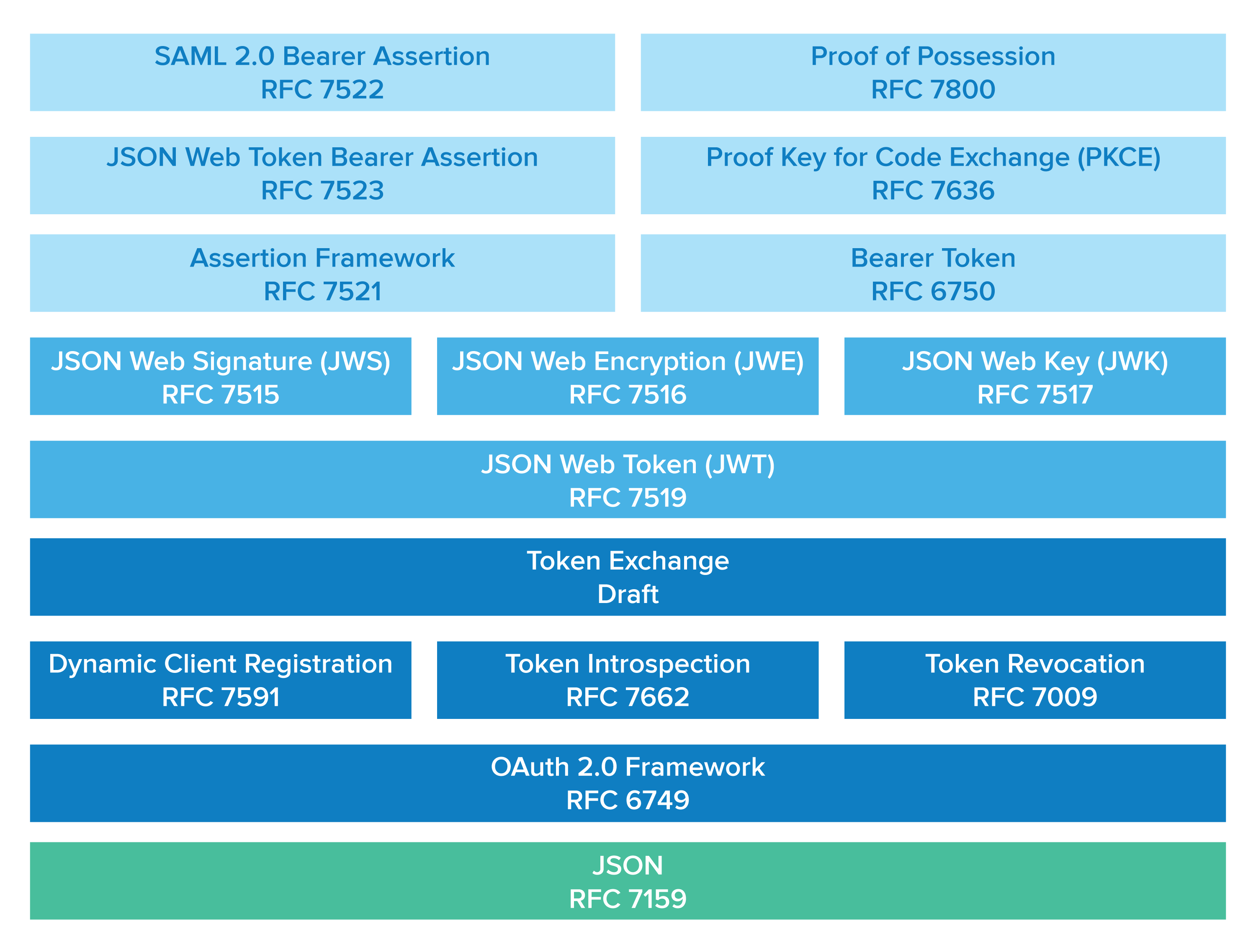

There's a huge number of additions that happened to OAuth in the last several years. These add complexity back on top of OAuth to complete a variety of enterprise scenarios. In , you can see how JSON and OAuth are the foundation. JWT, JWK, JWE, and JWS can be used as interoperable tokens that can be signed and encrypted.

Common Misconceptions about OAuth 2.0

OAuth 2.0 is not an authentication protocol. It explicitly says so in its documentation (opens new window).

While it's easy to lose that distinction, note that everything so far has been about delegated authorization. OAuth 2.0 alone says absolutely nothing about the user such as how they authenticate or what information we have about them. We simply have a token to access a resource.

Pseudo-Authentication with OAuth 2.0

Login with OAuth was made famous by Facebook Connect and Twitter. In this flow, a client accesses a /me endpoint with an access token. People invented this endpoint as a way of getting back a user profile with an access token. It's a non-standard way to get information about the user. There's no specification to support this and in fact, it was a originally a misuse of the standard networks. Access tokens are meant to be opaque. They're meant for the API; they're not designed to contain user information.

What you're really trying to answer with authentication is who the user is, when did the user authenticate, and how did the user authenticate. You can answer typically answer these questions with SAML assertions, not with access tokens and authorization grants. That's why it's called this pseudo authentication.

OpenID Connect (OIDC)

To solve the pseudo authentication problem, a number of social and identity providers combined best parts of OAuth 2.0, Facebook Connect, and SAML 2.0 to create OpenID Connect (opens new window) or OIDC.

Once again, despite the very similar name, OpenID Connect is not based on or compatible with the original OpenID specification. The name comes from the OpenID Foundation which promotes, protects, and nurtures the technologies and communities involved in identity on the web.

At a technical level, OIDC extends OAuth 2.0 with a new token called the id_token on the client application side and the UserInfo endpoint on the server side. They both benefit from having a specific, limited set of scopes and well-defined set of user-related claims. By combining them, an application can request information on a user's profile, email, address, and even phone number in a consistent way regardless of the OIDC provider.

OIDC was made famous by Google, Facebook, and Microsoft, all big early adopters. The single most important part is that the consistent scopes and claims make implementations fast, easier, and compatible regardless of the provider.

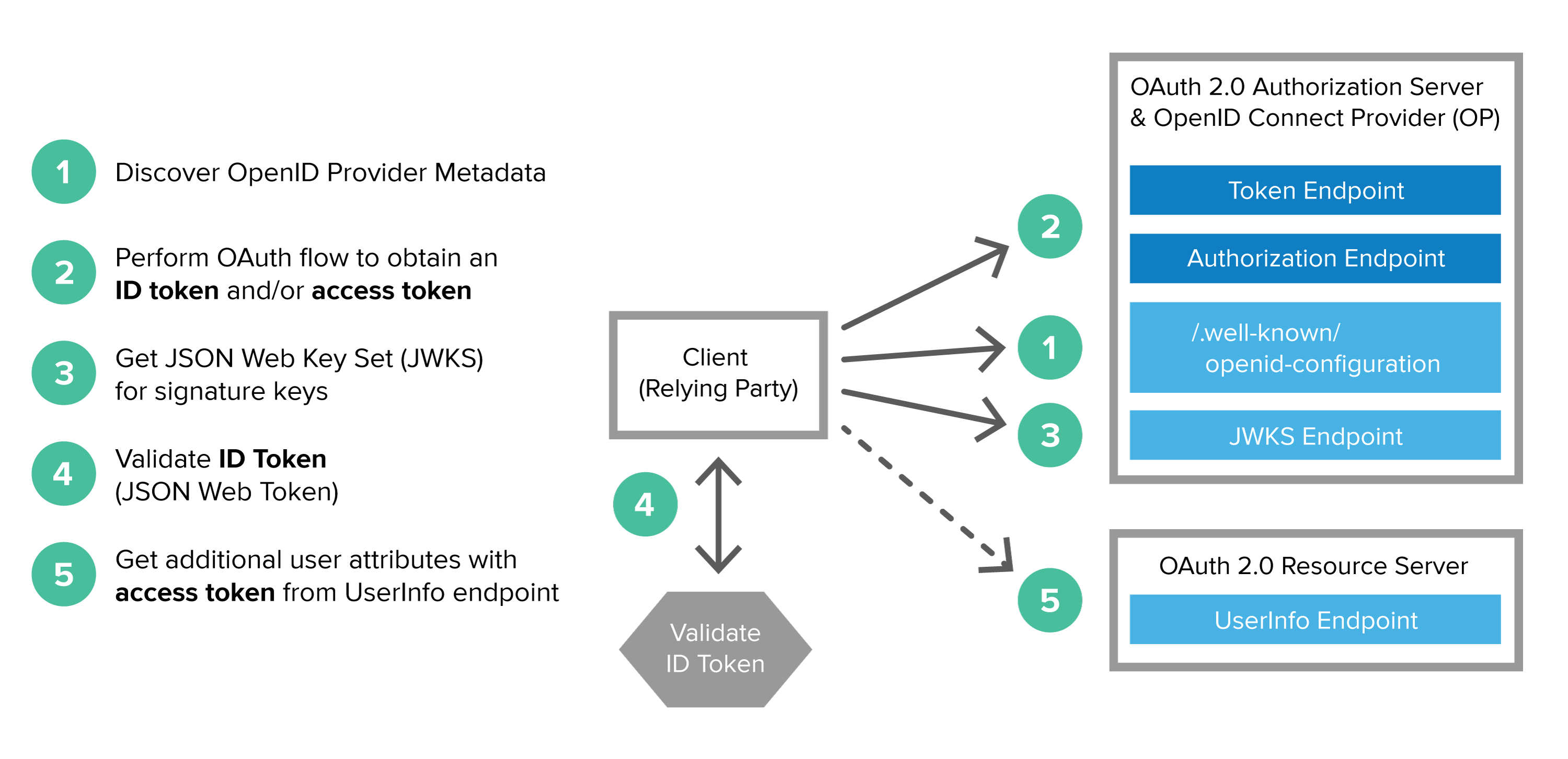

Generally, an OpenID Connect flow involves the following steps:- Discover OIDC metadata as defined in the specification (opens new window)

- Perform the OAuth flow to obtain id token and access token

- Validate JWT ID token locally based on built-in dates and signature

- Get additional user attributes as needed with the access token at the UserInfo endpoint

In terms of implementation, an ID token is a JSON Web Token (JWT) which adheres to the specification and is small enough to pass between devices

The Authorization Code flow can also be used with Native apps. In this scenario, the native app sends a PKCE code challenge along with the authentication request. PKCE (pronounced "pixy") stands for Proof Key for Code Exchange and is defined by RFC 7636 (opens new window).

OIDC is an excellent addition to and special case of OAuth because it allows you to get a user's information and learn more about them.